KESEY BOOK

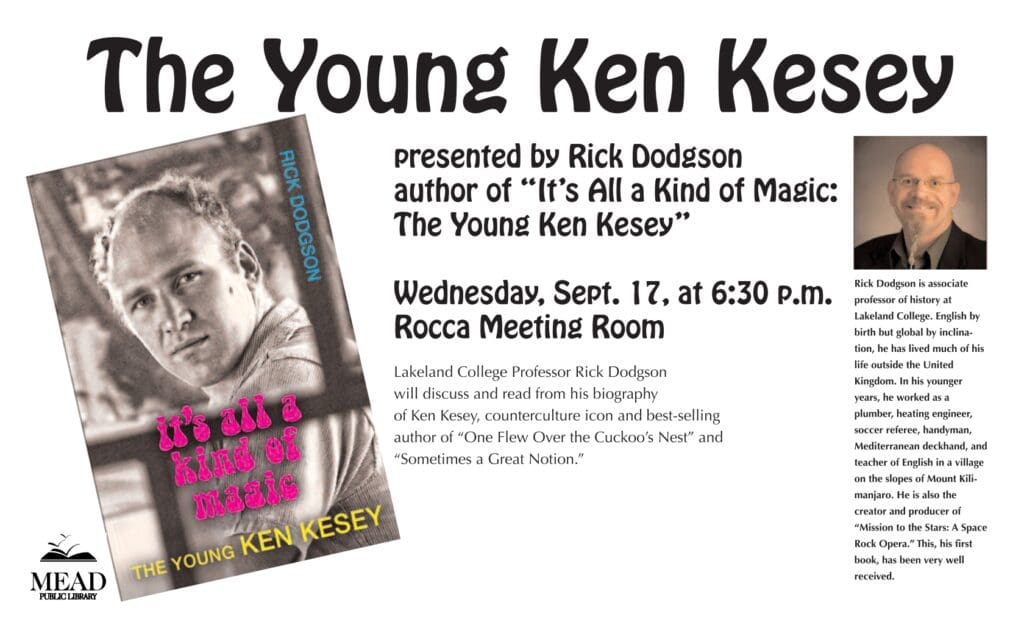

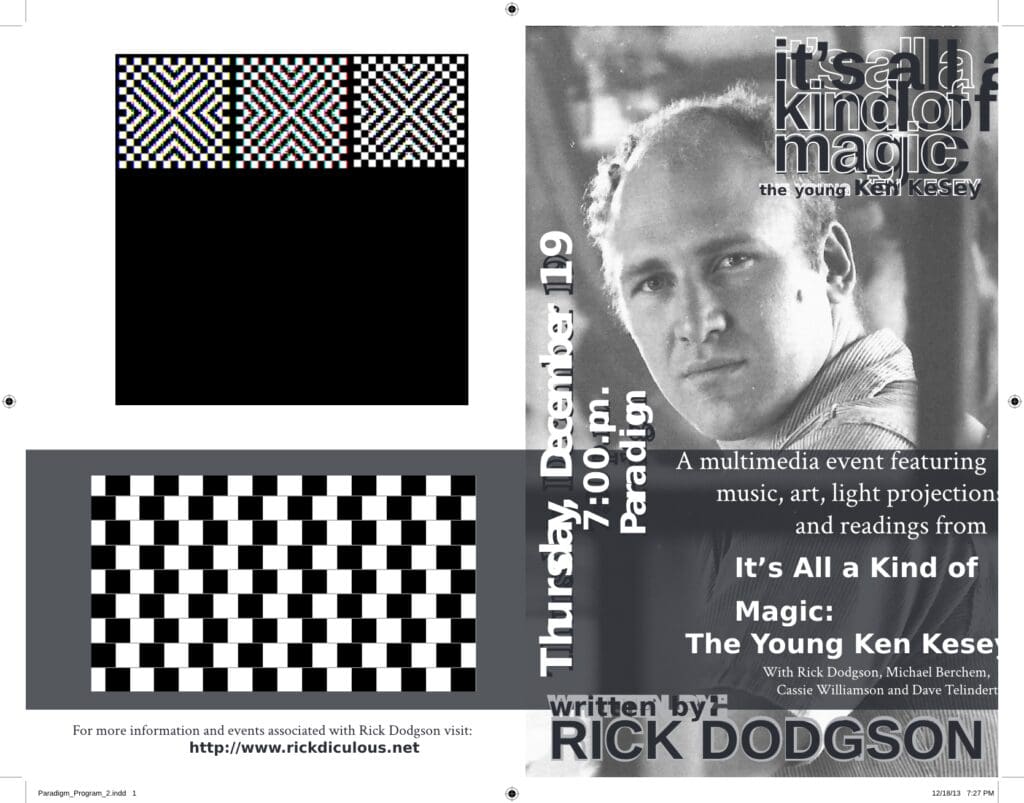

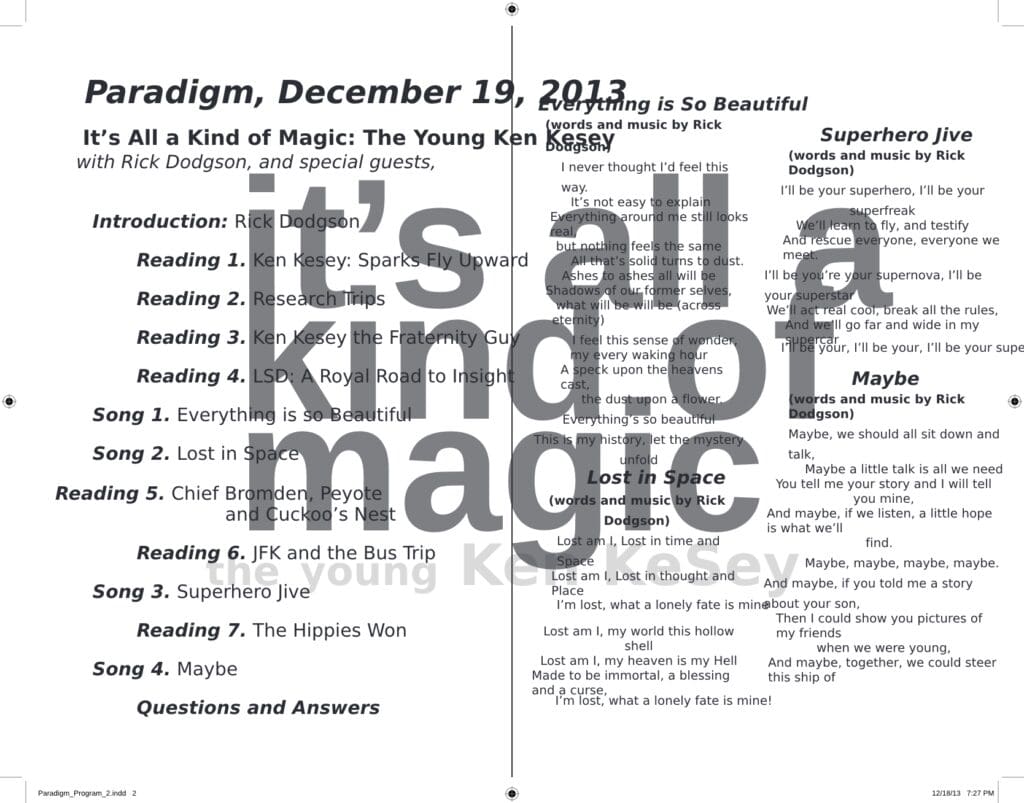

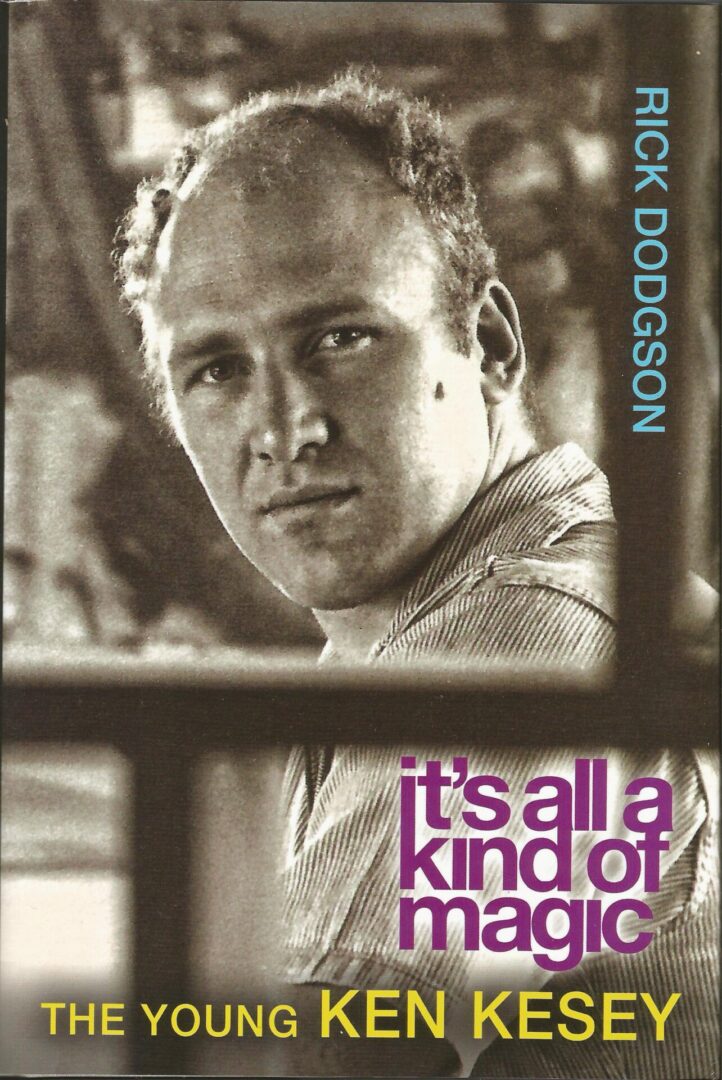

It's All a Kind of Magic The Young Ken Kesey

It’s All a Kind of Magic is a book about the early life of Ken Kesey, one of the most extraordinary characters in recent American history. Kesey came from relatively humble beginnings—he was a child of the depression, born to a migrant family who settled in Oregon during World War II—but by the time he was thirty, he had staked his claim on a place at the high table of American literature with the publication of two important novels—One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962) and Sometimes a Great Notion (1964).Both books remain classics of the 1960s, their anti-authoritarian sentiments an important reflection of their times.

As if that were not enough, Kesey also made his mark on history by being at the vanguard of a 1960s countercultural revolution that changed the world. He and his friends—the Merry Pranksters—were experimenting with psychedelic drugs and alternative lifestyles well before such activities became commonplace in the latter part of the decade. Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968) mythologized their adventures, casting Kesey and the Pranksters as the “source of it all.” Not bad for a dairy kid from Springfield, Oregon!

Illustrated with an incredible collection of photographs, based on extensive archival research and interviews with friends, family and fellow Merry Pranksters, It’s All a Kind of Magic describes the early life of Ken Kesey, from his time growing up in Oregon, through his college years, to his first drug experiences in California, and to the writing of his most famous books. What emerges is a fascinating picture of a precocious young man, brimming with self-confidence and ambition, who through talent, instinct and good fortune carved himself a role in history like few others before or since.

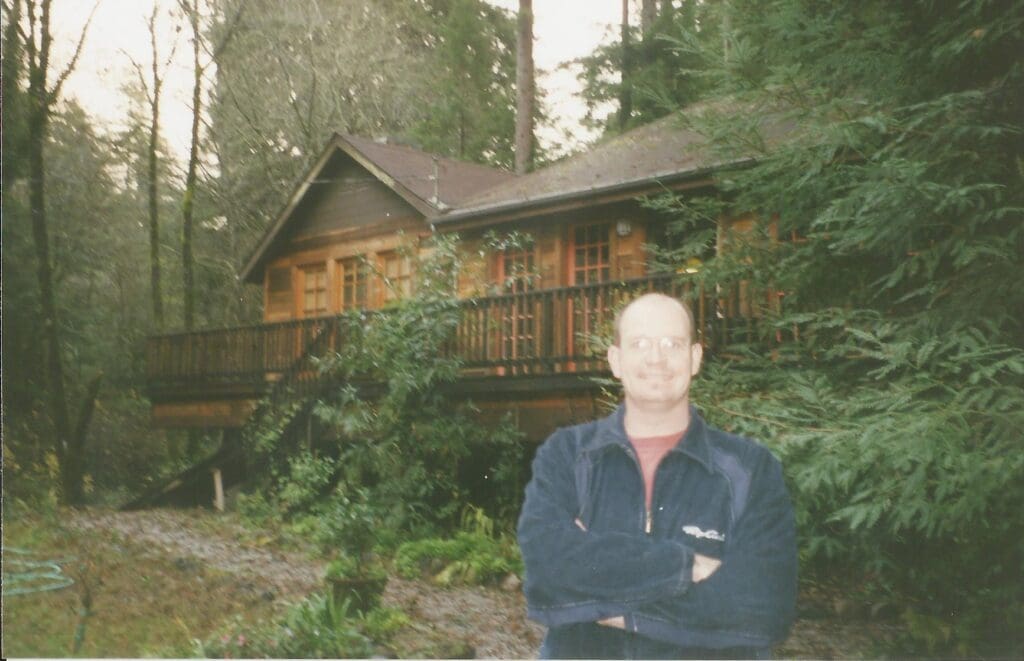

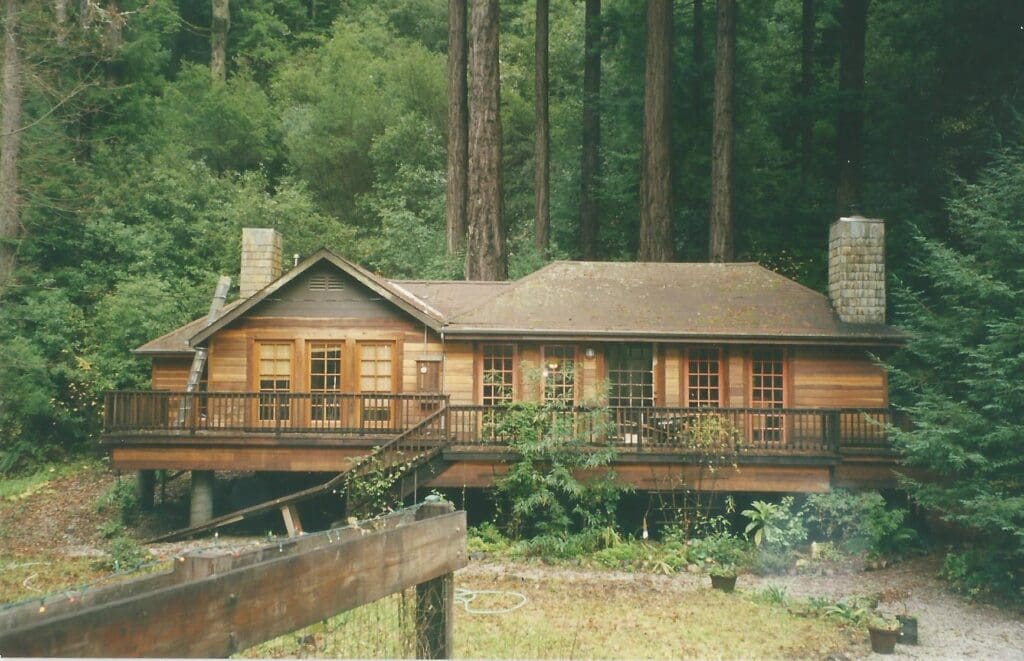

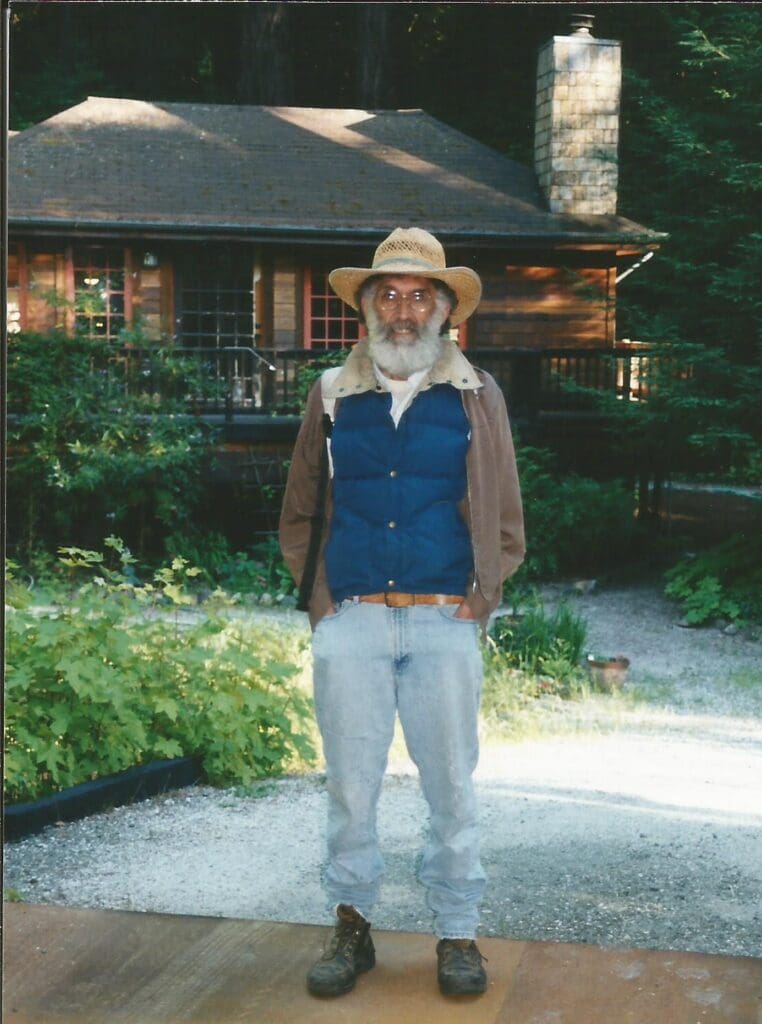

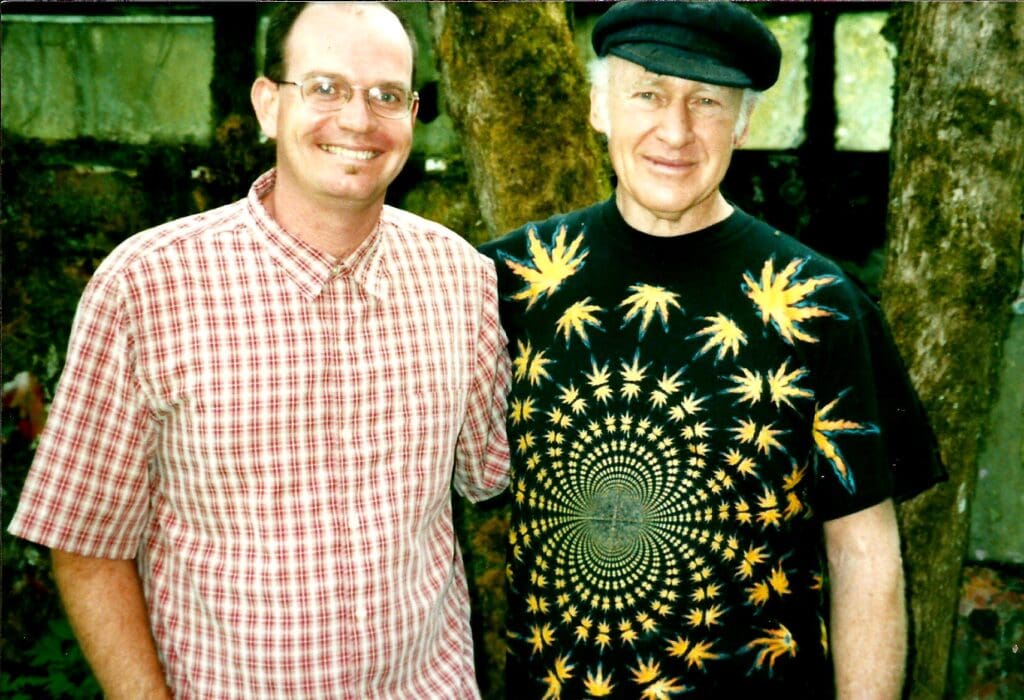

Read the Preface below to learn how I first met Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters and view images from my research trips out West. An additional sample chapter, The Mavericks of La Honda, recalls Kesey’s move to a new home in the redwood hills of La Honda, CA in 1964, described by Hunter S. Thompson as the “world capital of madness,” where “there were no rules, fear was unknown, and sleep was out of the question.”

Please contact me directly if you are interested in booking me for a reading of my book or a presentation of my research on Ken Kesey, the Merry Pranksters and the 1960s.

Reviews

Preface

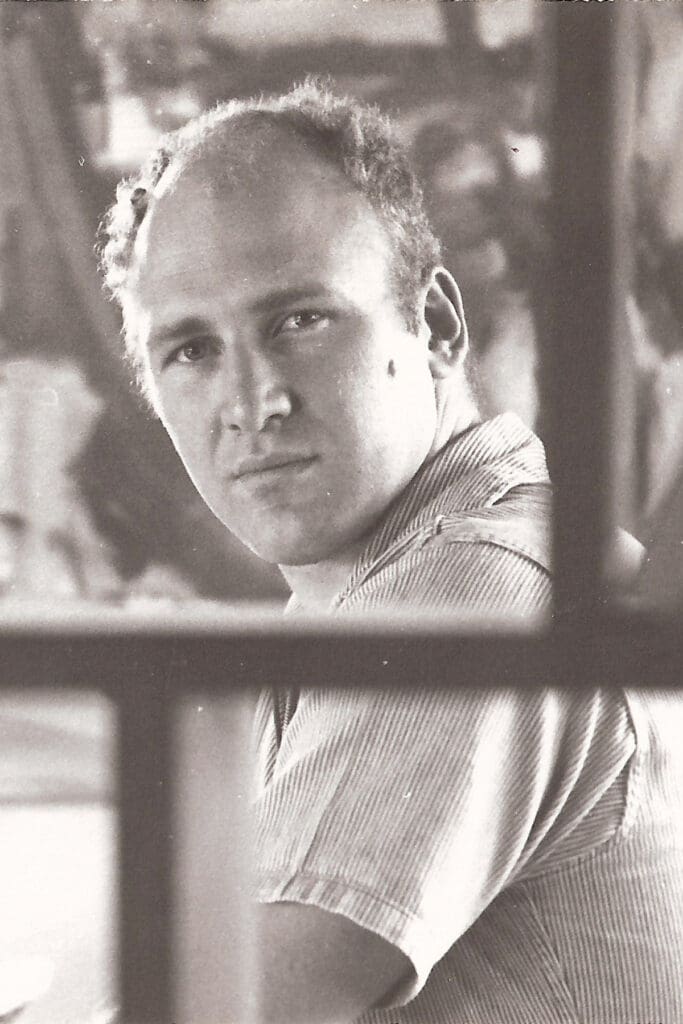

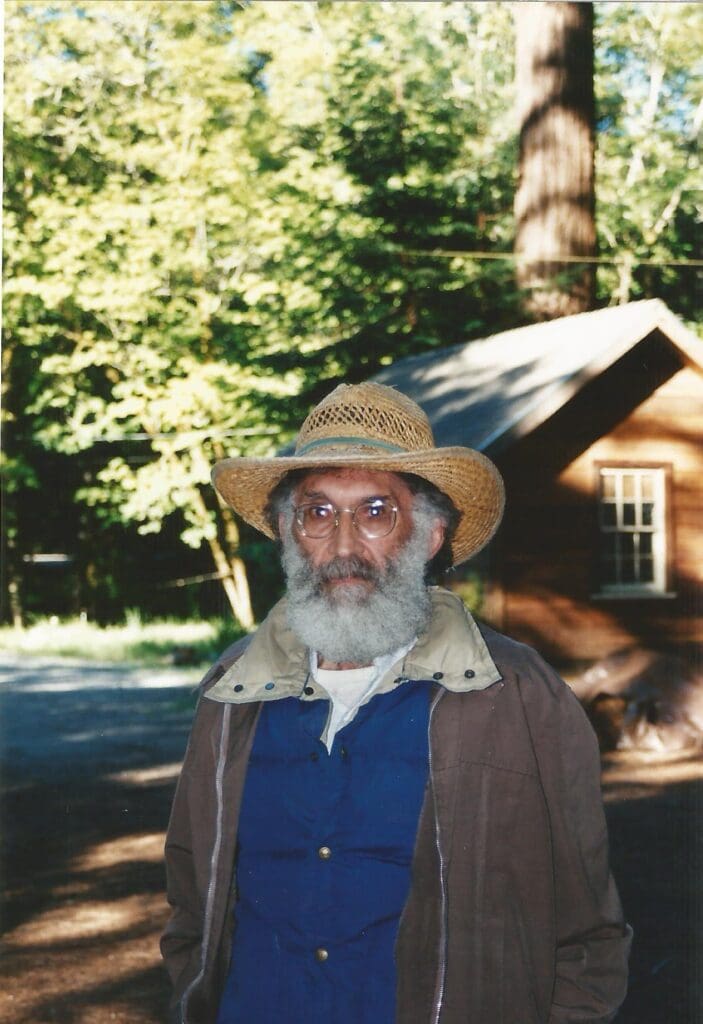

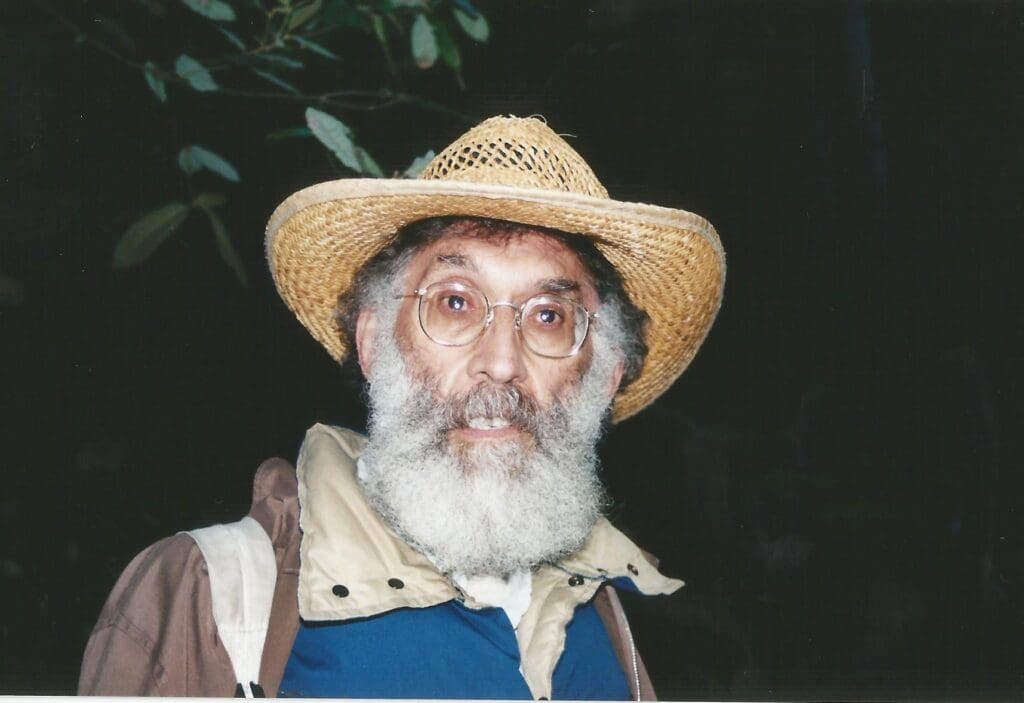

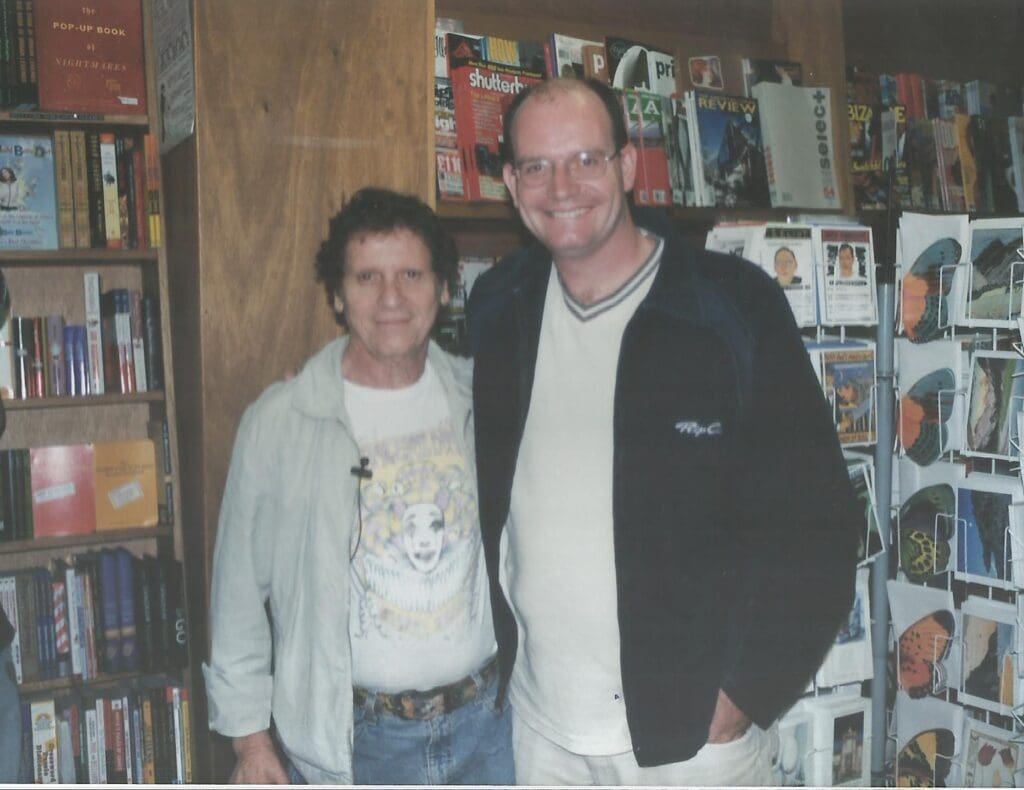

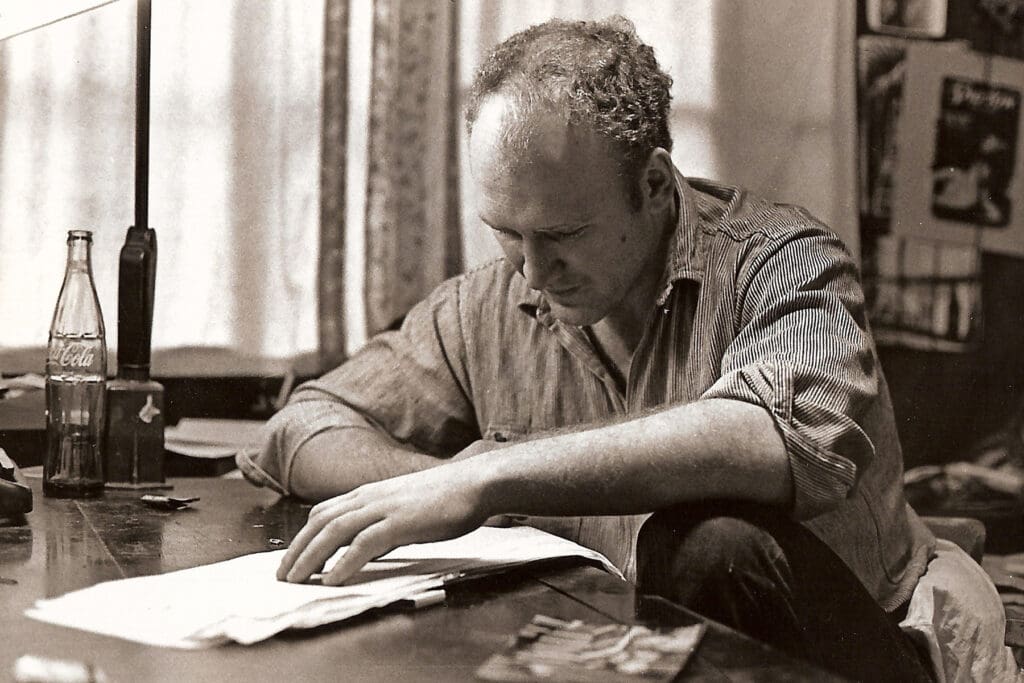

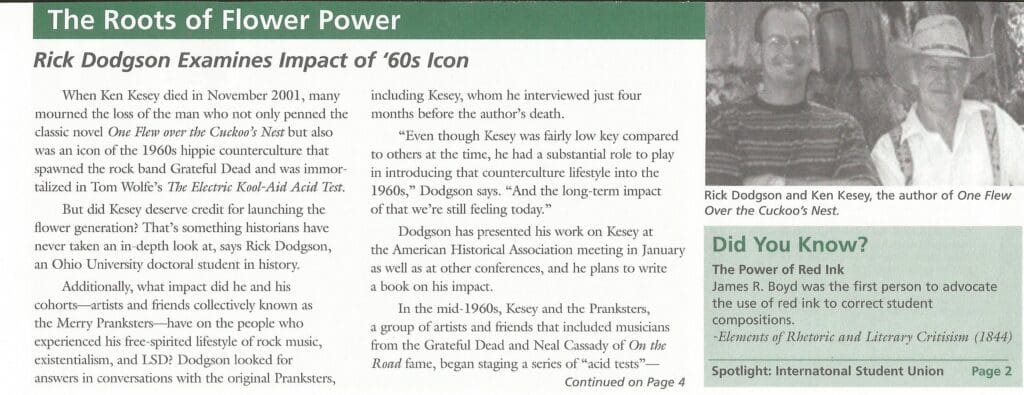

I first met Ken Kesey in the summer of 1999. I had just started graduate school at Ohio University—in Athens, Ohio—and I was casting about for something sixties-related to write about for my PhD dissertation. I had initially considered writing about some of the intentional communities that had sprung up around Athens in the late 1960s, but then I discovered Kesey’s website, IntrepidTrips.com. Having already read One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Tom Wolfe’s Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, I was well aware of Kesey’s role in the history of the 1960s. I was surprised to find that nothing substantial had been written about his adventures since Wolfe’s book came out in 1968. A substantial body of work devoted to scrutinizing Kesey’s written work had emerged in the 1970s, but there was no sign of a serious biography, or a proper history book devoted to this supposed “father of the counterculture.” This is what historians like to call a “gap in the literature.” I wrote Kesey an email to introduce myself, just a stab in the dark really, but to my amazement he responded. We corresponded briefly; me desperate to impress, he willing to write back quick one-liners without ever really answering my questions. After a few weeks of this email cat and mouse, he finally agreed to meet, inviting me to come and visit his farm in Pleasant Hill, Oregon. He had still not agreed to be the subject of my dissertation, and I had become convinced that the only way to get him to seriously consider my request was if I asked him in person, face to face.

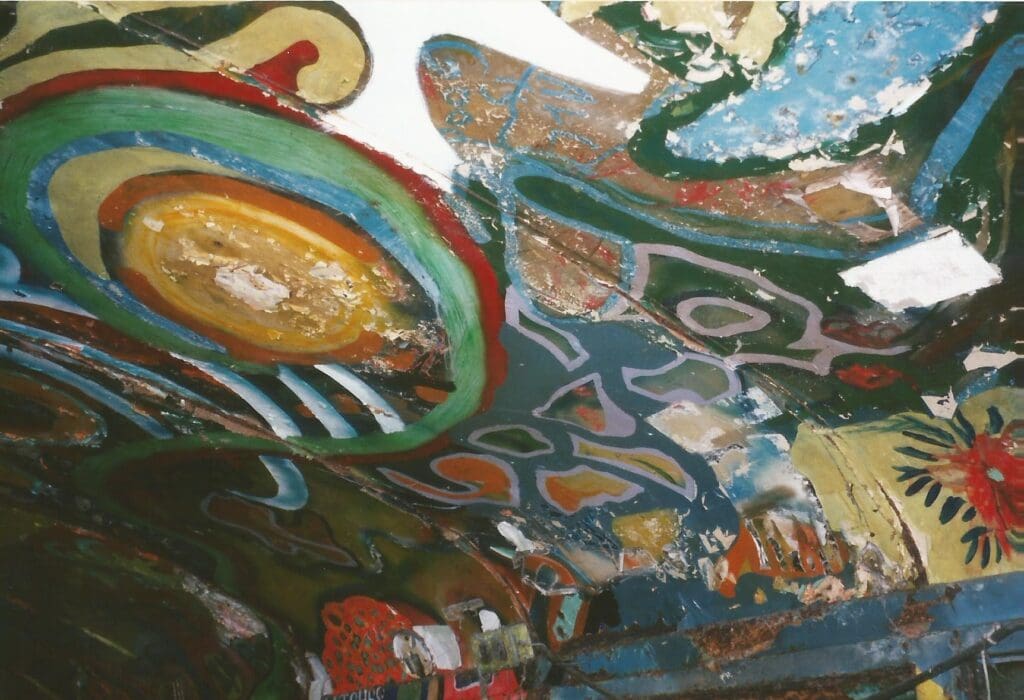

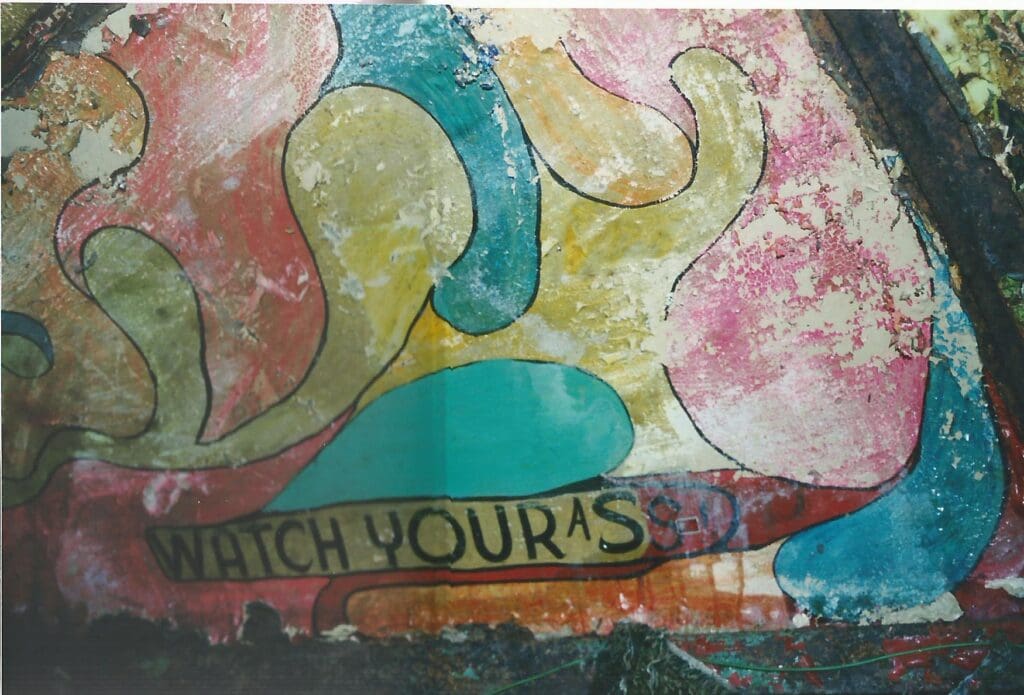

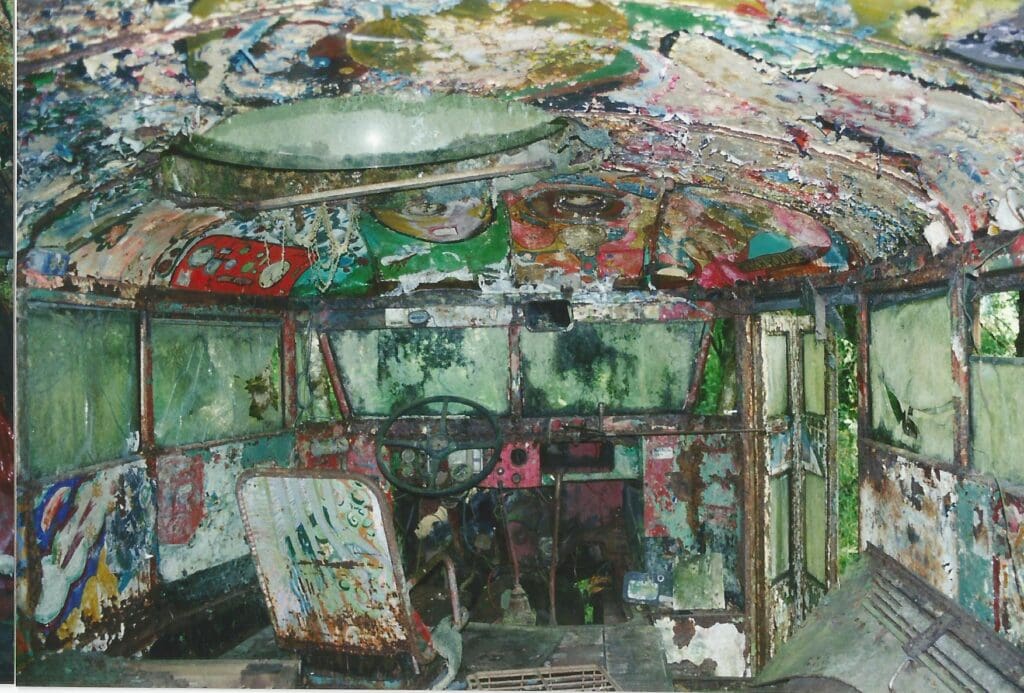

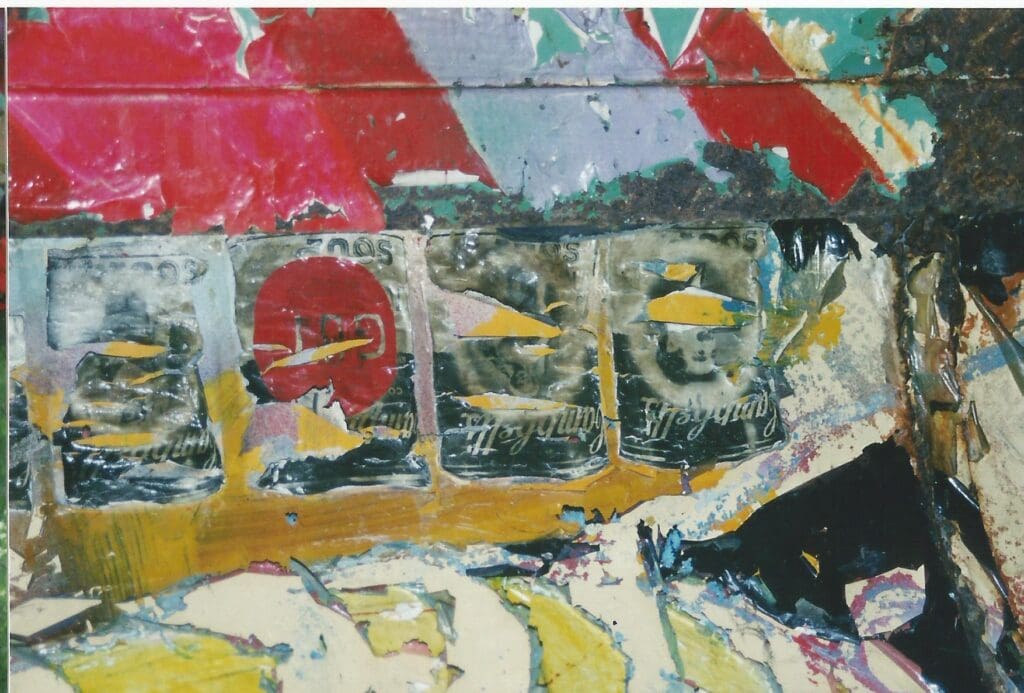

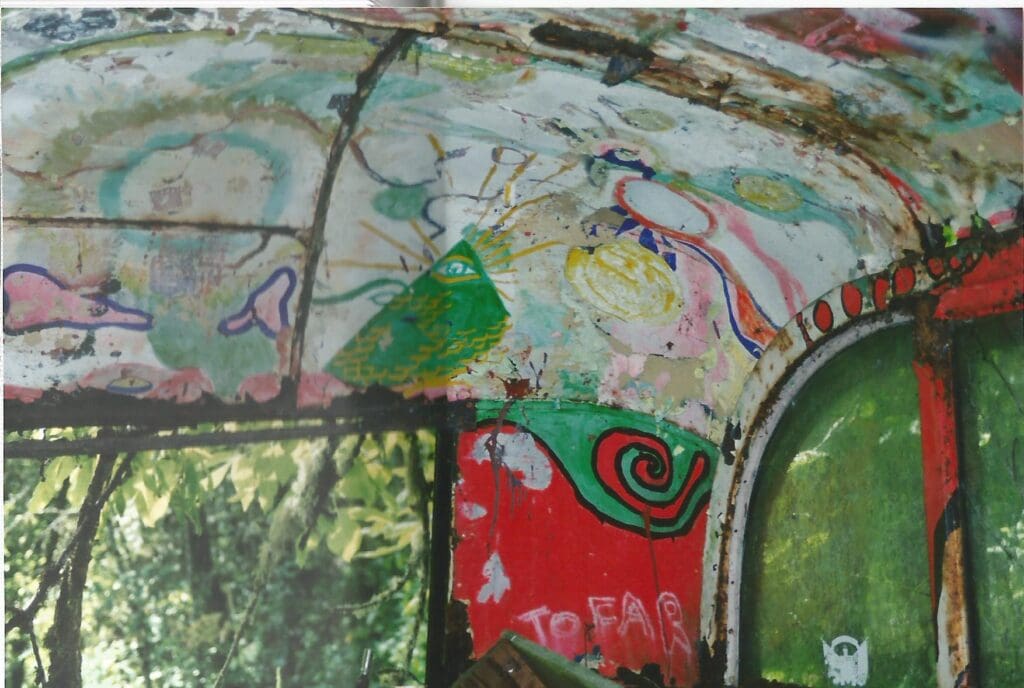

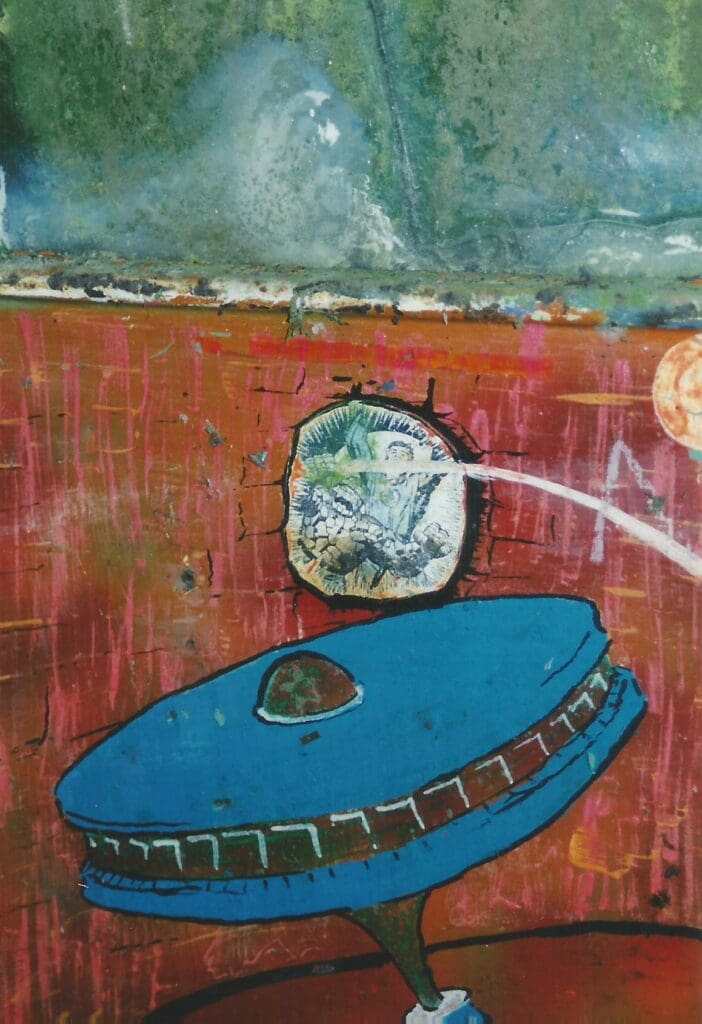

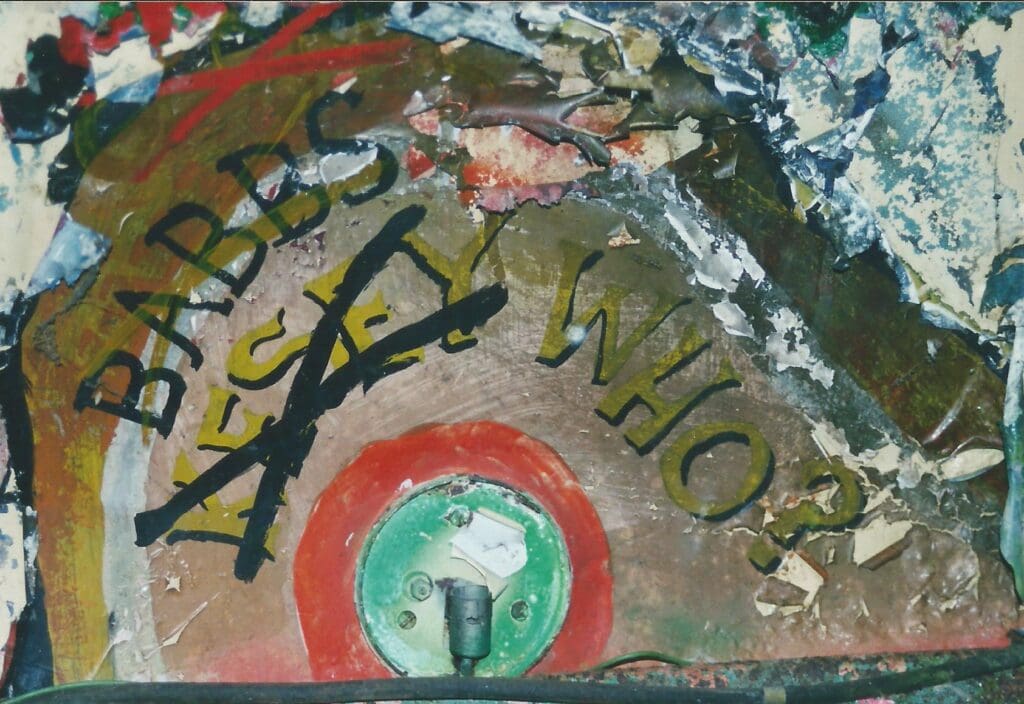

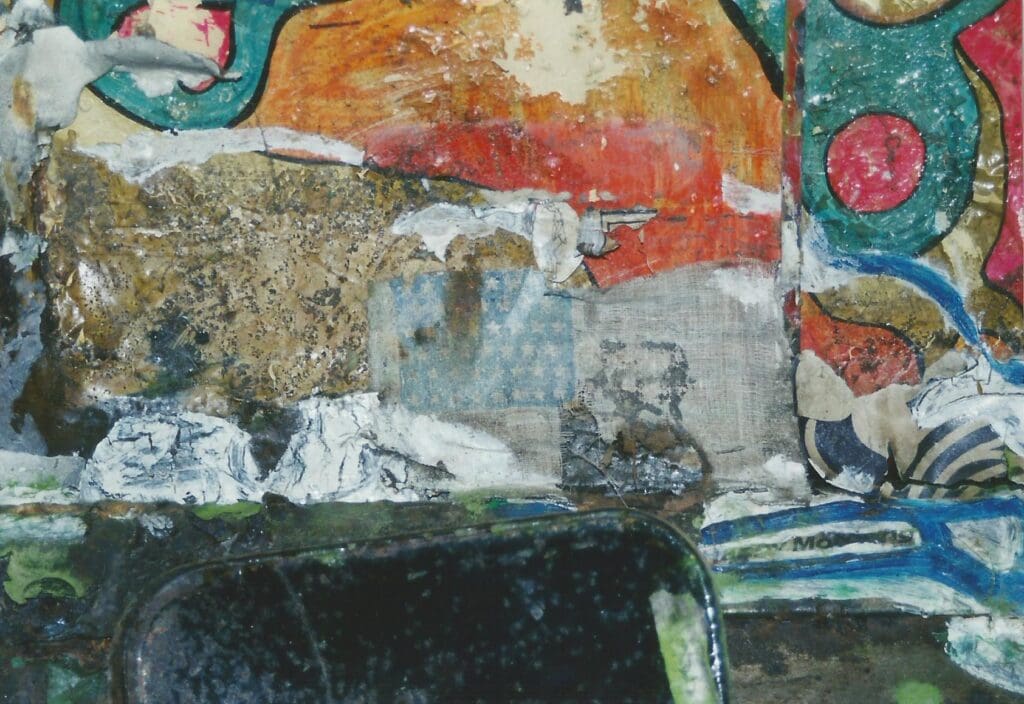

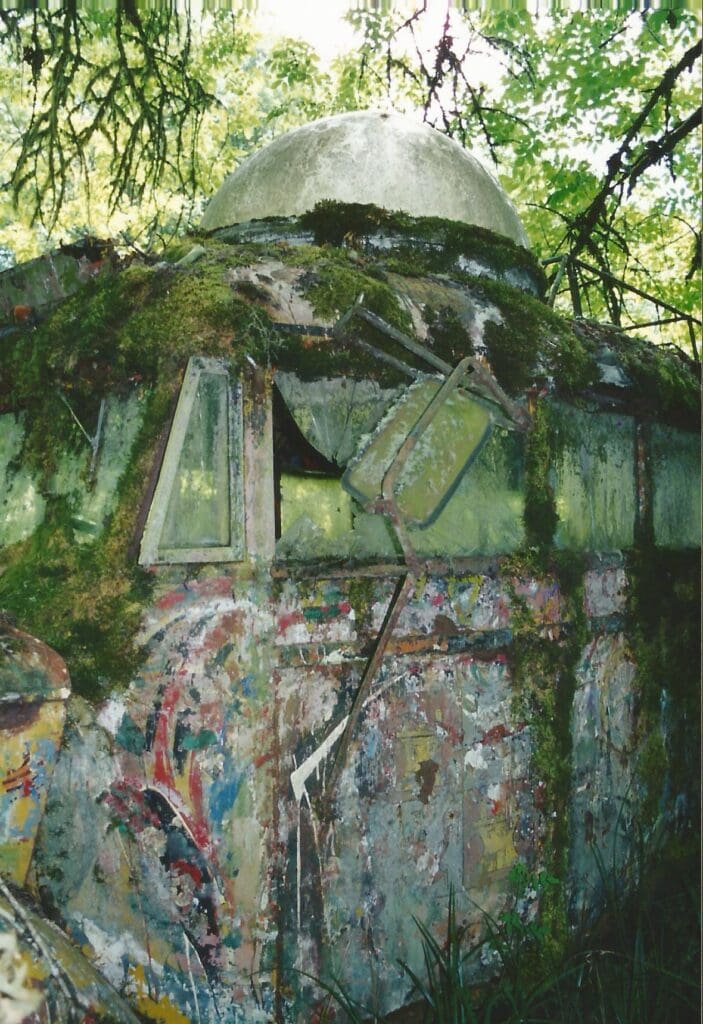

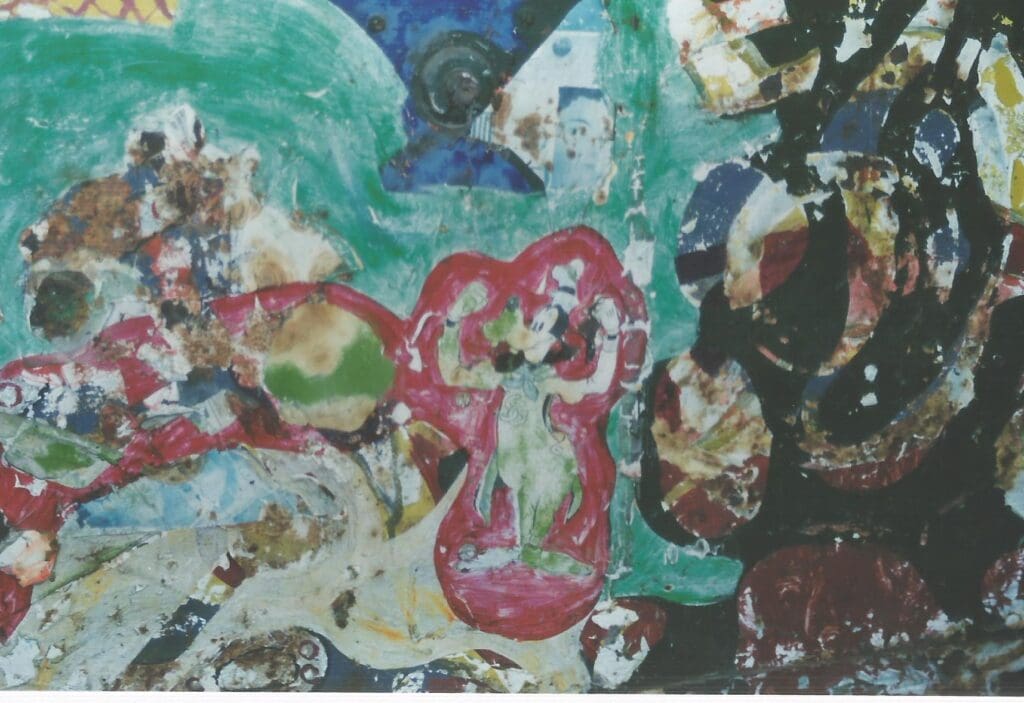

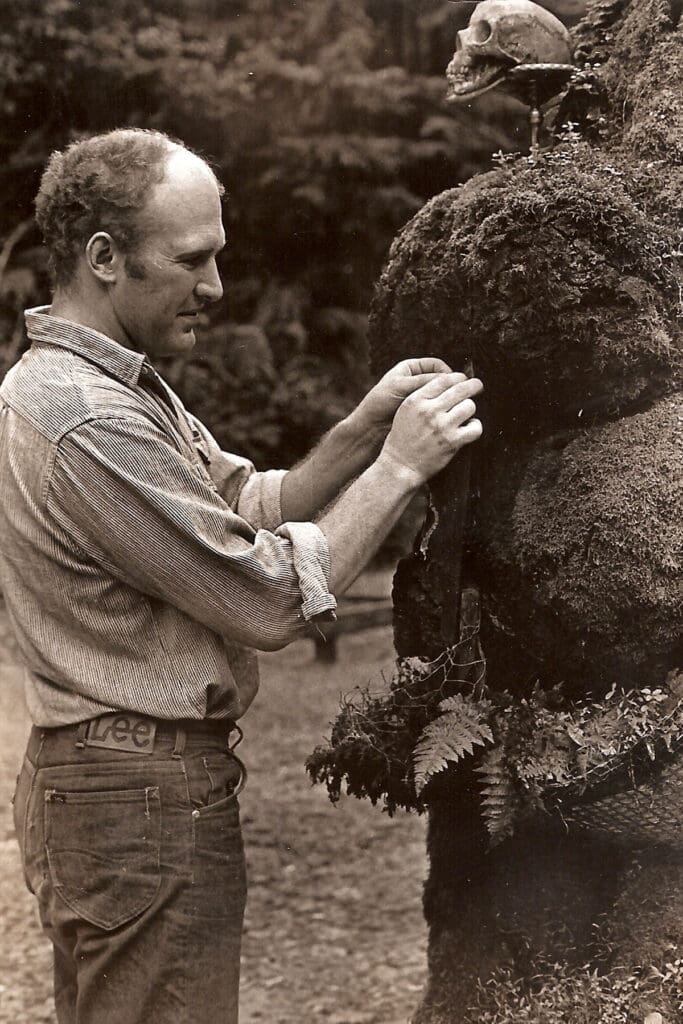

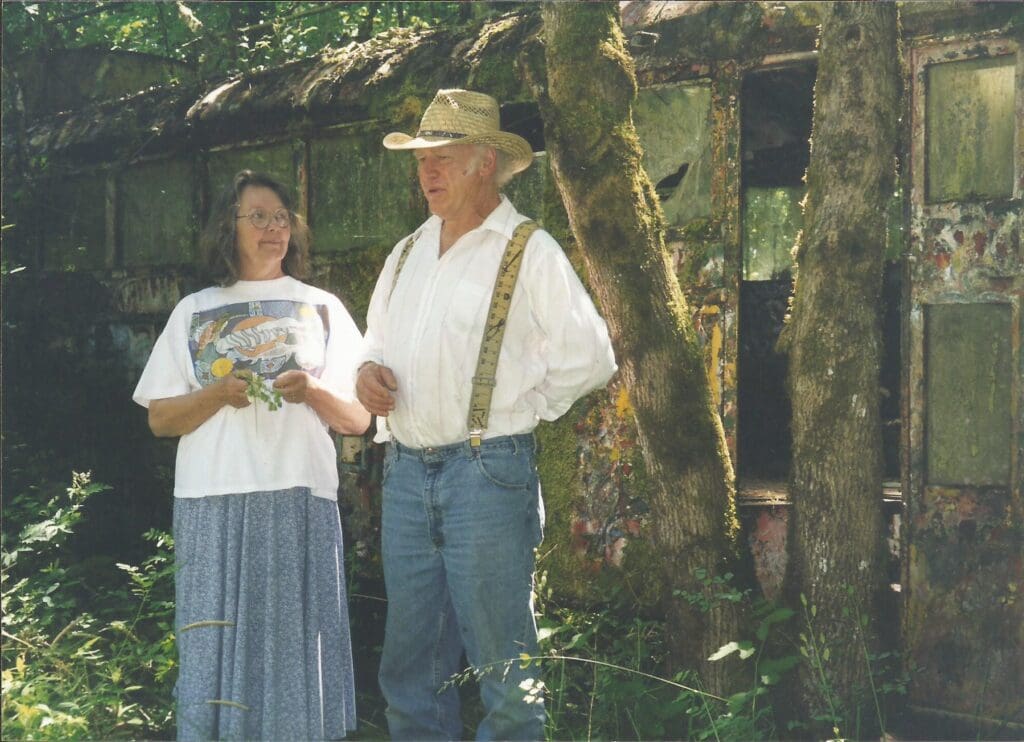

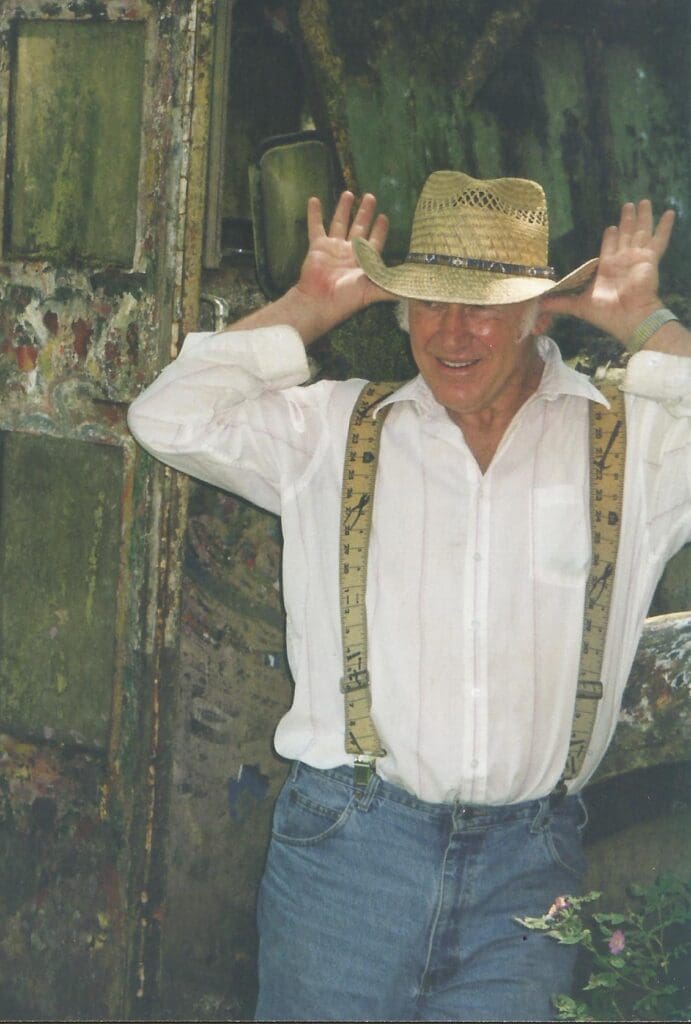

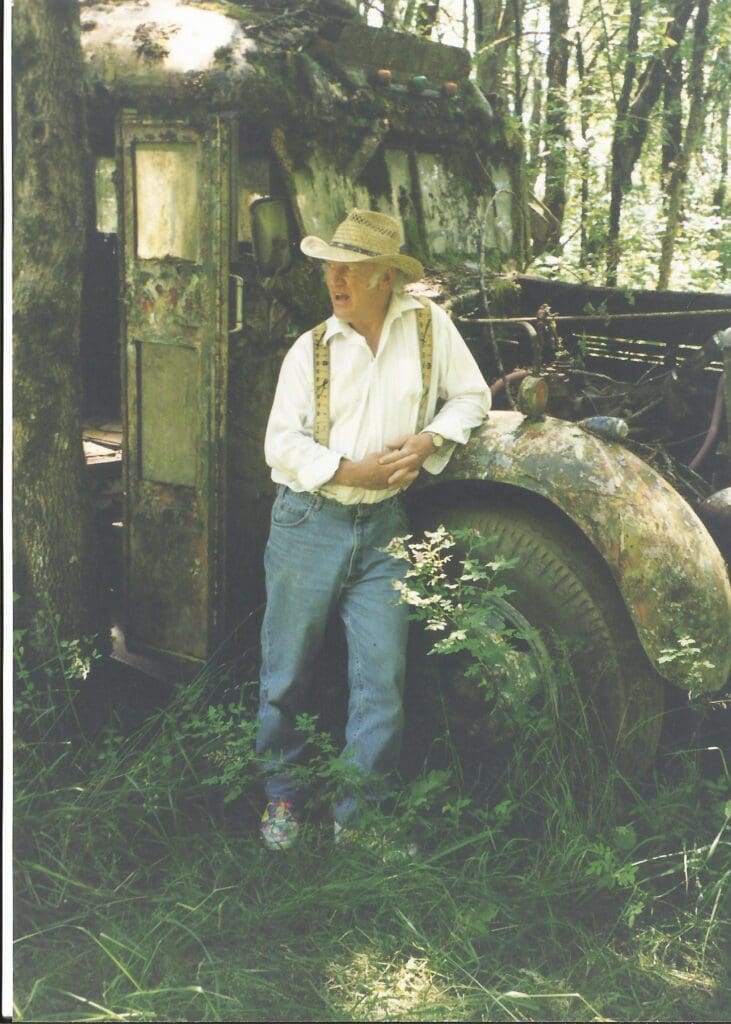

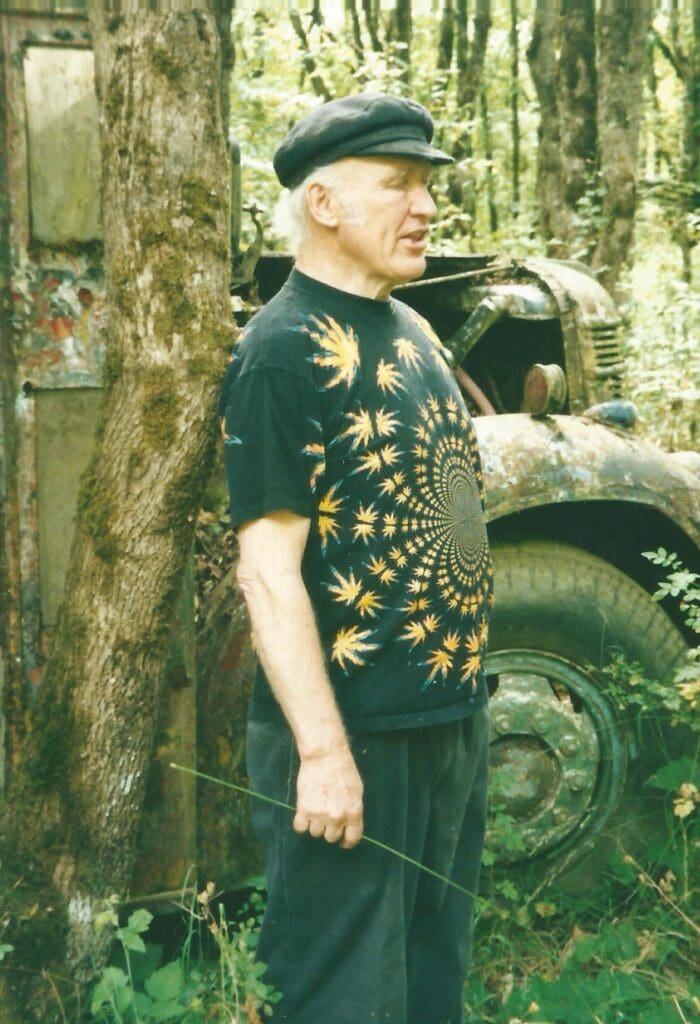

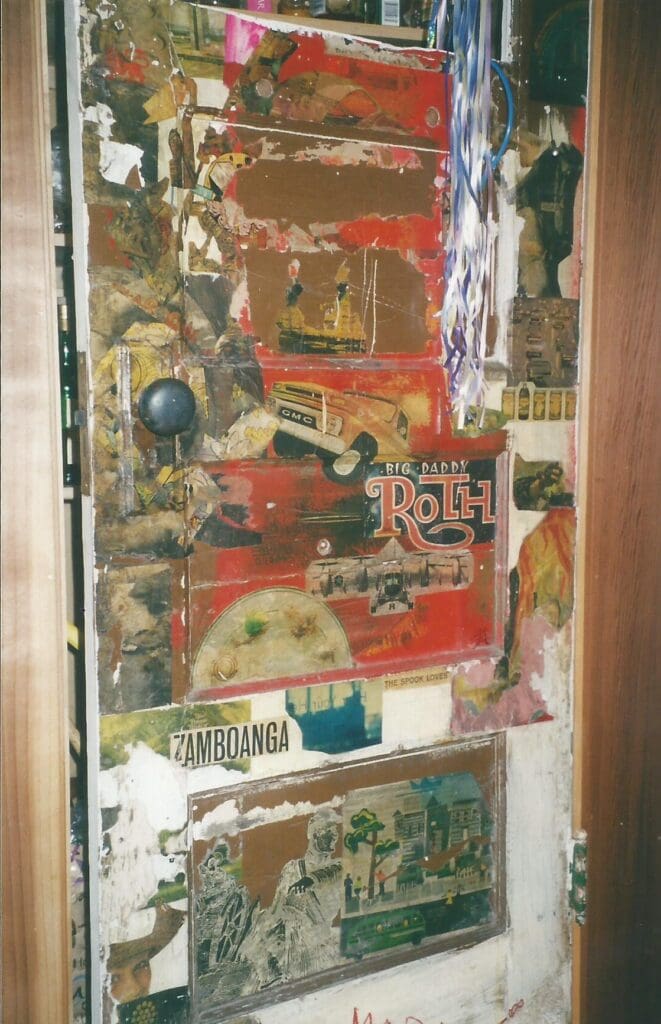

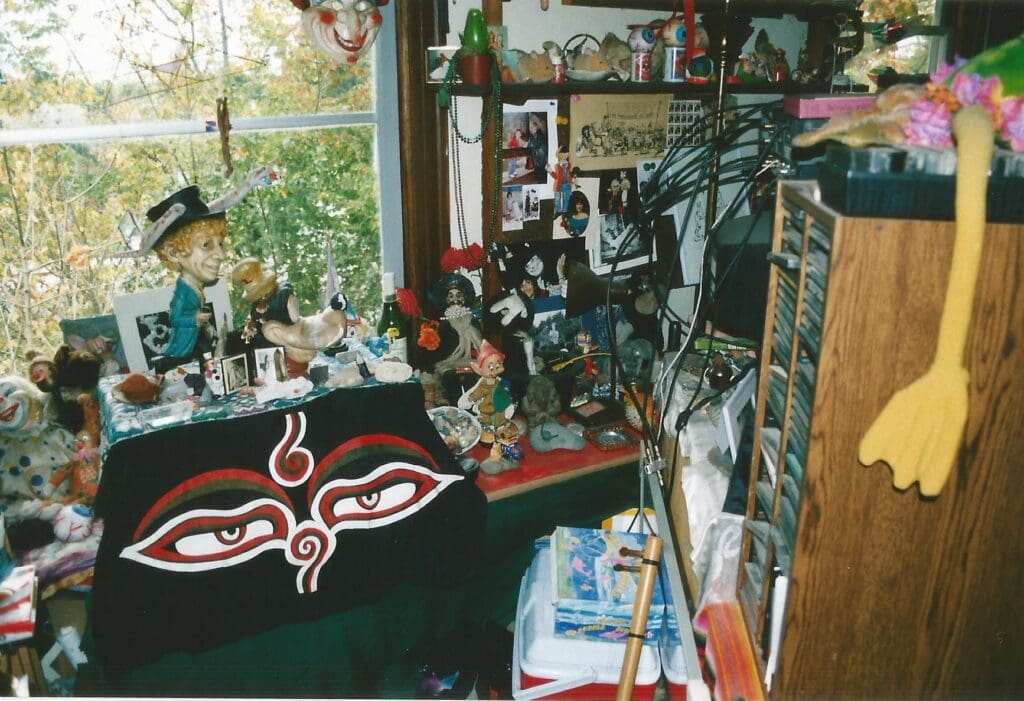

With that thought in mind, my family and I set off in our van to drive across the country to meet the man. I could have flown on my own, but the family road trip seemed far more appropriate, and a whole lot more fun. We arrived in late June, to find Kesey busy in his preparations for a trip to England. He and the surviving Pranksters, many of whom also lived in Oregon, had got money from a British TV company to ship themselves and their bus—a second generation Further—over to the U.K. as part of a series celebrating the Summer of Love. I was nervous to meet Kesey, but he was welcoming and approachable. He took me out to the garage to show me the new bus—the original Furthur lay rotting in some woodland on the other side of the house—and then he led me into an archive room in the garage that was full of old journals, papers, photos and reels of vintage film and audio tape. The room had been constructed to be fire-proof, but I remember that the heavy metal door was propped open, defeating its whole purpose. Kesey pulled out a heavy looking notebook from a cardboard box, explaining that this was his personal diary from the mid-to-late 1950s, when he was a Speech and Communications major at the University of Oregon (U of O), located just a few miles away in Eugene. Inside the book, Kesey’s untidy teenage handwriting filled page after page, detailing his everyday activities and his every thought. Wow! The budding historian within me knew that I was looking at an incredible historical resource: an unfiltered, personal account of the past, an insight into the young mind of an important historical actor. This journal was the sort of Holy Grail artifact that all historians dream of discovering. Kesey did not seem to care too much. He tossed the book back into the box, and suggested we go to meet Ken Babbs, his right-hand Prankster.

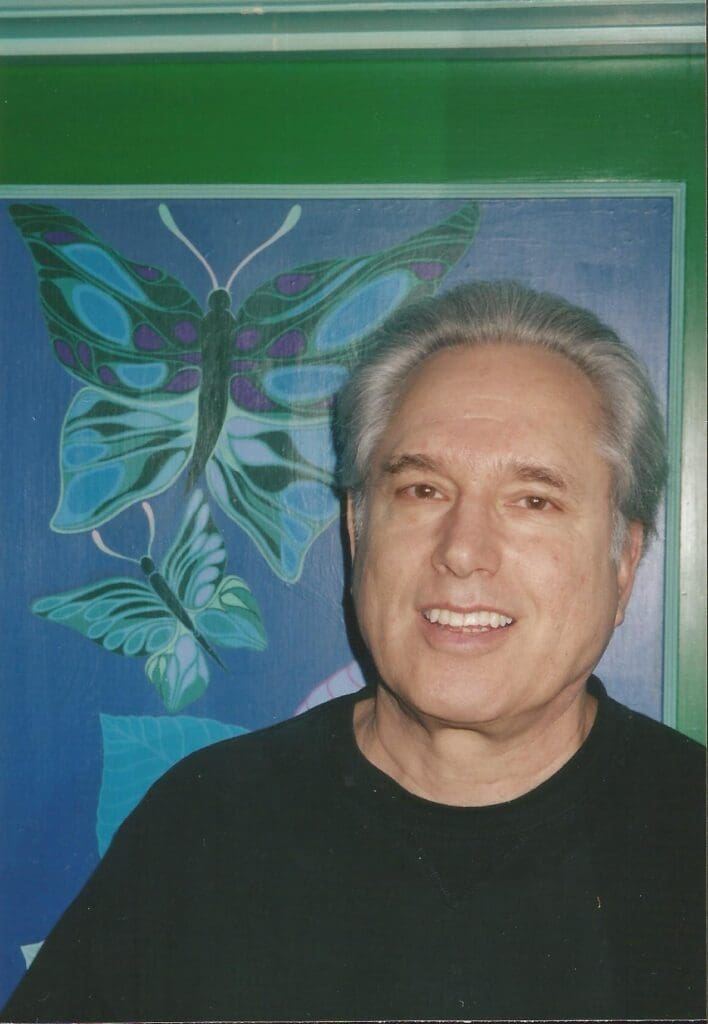

Babbs lived a few miles away in a place called Dexter, in a house he had built himself on a nice piece of land next to a running stream. Sitting in Babbs’ kitchen, I finally got up the courage to ask the big questions. First, I wanted to know whether Kesey was writing an autobiography, or working with a biographer or historian already. If he had said “yes,” I knew that I would have to find something else to write about for my dissertation, but he simply shook his head, indicating “no.” So far, so good. Second, I wanted to know whether he would be willing to help me if I decided to make him the subject of my own writing. I knew that this was important, because without Kesey’s co-operation, I doubted that anyone else was going to co-operate either and my dissertation would be a non-starter. When asked to describe my project, I explained that I hoped to write about the history of Kesey and the Merry Pranksters as part of my graduate studies in history. Asked if I was writing a book, I explained that if I pursued a career in academia, as I hoped to do, then the possibility existed for my dissertation to be published as a book. But at this time, such a possibility remained a distant ambition. Kesey and Babbs looked at each other briefly, shrugged, and nodded in assent, in a very matter-of-fact fashion. This was not the most expressive or enthusiastic sign of support, but it was far better than a “no,” and there was more to come.

Kesey and Babbs took me to the IntrepidTrips office, a small shop-front close to the post-office in Pleasant Hill. Here, they had assembled some computers and some film and audio editing equipment. With the assistance of some of their grown-up kids, they had started producing videos out of all the footage they had shot of their famous cross-country bus trip in 1964. Kesey showed me some footage of Neal Cassady—the real life Dean Moriarty from Jack Kerouac’s On the Road—who had been the driver on that trip. The footage was shaky and grainy, but it clearly showed Cassady, shirtless and excited, driving the original Furthur bus up the New Jersey turnpike, with New York looming in the distance. Another wow moment! While Kesey expounded on Cassady, describing him as an avatar—a deity in human form—I could not take my eyes off the computer screen, witnessing for the first time the famous Cassady in action. The audio captured Cassady in the middle of one of his endless pun-filled raps, commenting on everything around him and whatever came to mind: the traffic, shifting gears, past adventures, ideas for a movie script, literary references, and extemporaneous philosophical musings.

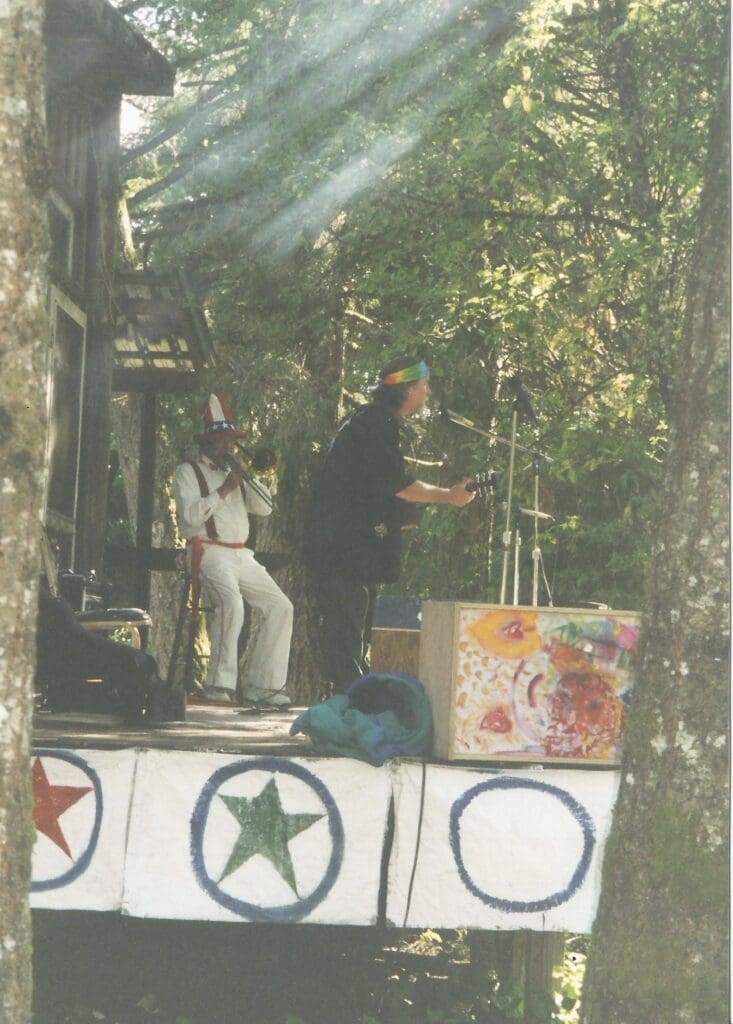

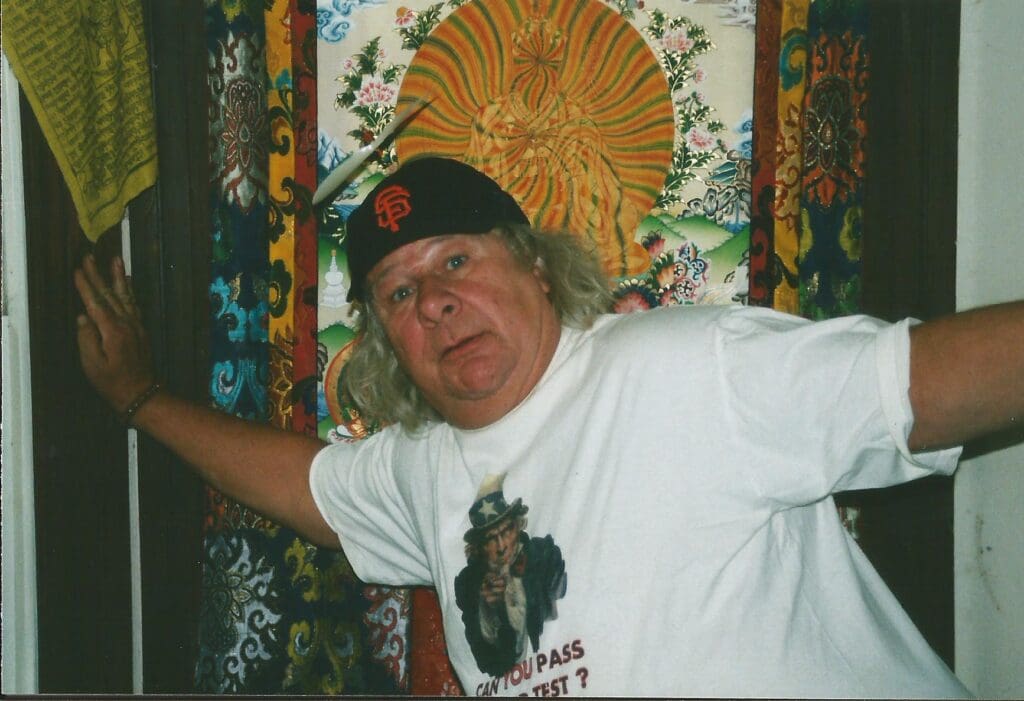

Amazing! Kesey told me that they planned to release a whole series of videos and CDs culled from their film and audio archives, everything from the Bus Trip to the Acid Tests and beyond. Later that night, I returned to Kesey’s farm to witness a rehearsal for a play that Kesey had written—The Search for Merlin—that he and his Merry Prankster friends planned to perform on their UK trip. Among the players were some “new” Pranksters, such as Phil Dietz and John Swan, and many of the originals: Mike “Malfunction” Hagen, Carolyn “Mountain Girl” Adams, Ken Babbs, Roy Sebern, “Anonymous,” and George “Hardly Visible” Walker. I could not make much sense of the performance, which was far from polished, but I was delighted to witness the Merry Pranksters, these famous countercultural icons, all together in the same room, laughing and fooling around together, just like back in the day. Kesey was still clearly the leader of the group, and the director of their production, but the atmosphere was relaxed and playful. Back in the farmhouse, Faye Kesey, Kesey’s wife, had prepared a meal for everybody. While we ate, Kesey and the others peppered me with a few questions about England—my country of origin—in preparation for their trip. I don’t remember saying anything particularly useful, but I was able to tell them all about the spectacular Minack Theatre in Cornwall, an outdoor amphitheatre perched on the cliffs above the ocean, where they were booked to give a performance on August 1 to coincide with a rare solar eclipse.

My family and I spent the night in our van, parked by the bus garage on Kesey’s farm. I was so excited that I could barely sleep. I was thrilled to meet Kesey and the Pranksters and elated by the prospect of writing about their adventures. The following day, I tried to broach the subject of an interview with Kesey, but he was reticent. Faye had already warned me that if I had questions, I should probably ask them along the way, rather than expect Kesey to sit down and talk. Instead, while Kesey went off to cut the grass around his house, he invited me to spend time in his archives, looking at the journals and papers that he had shown me the previous day. He did not need to ask me twice. I was anxious to speak to him more formally, but I knew that the real historical treasure existed in those archives. I spent the rest of the day in there, reading through journals that documented most of Kesey’s life, including I-Ching journals where he recorded his daily readings. The best journal by far was the one from the 1950s, written before the distractions of adulthood, fame and family kept Kesey from devoting as much time to his diary. There was much more besides Kesey’s journals: copies of letters that he had written to Larry McMurtry while he was on the run in Mexico in 1966; a suitcase full of hundreds of photos; random files of newspaper clippings; one of Mountain Girl’s journals from the mid-sixties; a few old posters and fliers—including an original Acid Test flyer from 1966—and all sorts of videos and cassettes, including some recorded during the Grateful Dead’s trip to Egypt in 1978, when the group played in front of the pyramids. A box of old reel to reel tapes contained even older recordings. One marked “Kerouac New York Party” hinted at the incredible amount of history that was kept in this room. It was overwhelming, really.

The next day, at the urging of both Kesey and Babbs, I went to visit the Special Collections library at the University of Oregon. In 1973, Kesey and Babbs deposited all their old papers there, creating a collection called the Ken Kesey Papers 1960 – 1973. This was another incredible archive of great material, some of which actually dated from the mid-1950s, despite the name of the collection. The papers included at least ten folders of correspondence from the early 1960s, much of it between Kesey and Babbs, but there were also business letters, fan mail, and letters to and from family. Faye Kesey had spent time in the collection, attempting to put dates on Kesey’s letters, and working with an archivist to provide contextual information for scholars working with the papers. The collection also included short stories and essays, mostly unpublished, that Kesey had written at college; a collection of more than twenty tape recordings made by Kesey and friends in the early 1960s; the original manuscripts for Cuckoo’s Nest and Sometimes a Great Notion; sketches that Kesey had drawn of people on the hospital ward when he was writing Cuckoo’s Nest; a manuscript for Zoo, an unpublished novel Kesey wrote at Stanford before he started work on Cuckoo’s Nest; an outline and sample chapter for One Lane, an unfinished and unpublished project that Kesey started working on before the 1964 bus trip; and a whole bunch of other notebooks, drawings and random papers.

For the second time in a couple of days, I found myself staring at an incredible collection of primary historical resources. Kesey gave me written permission to obtain photocopies of some of these materials, and so I identified a few choice pieces and gave the archivist a list. This was an expensive process, so I could only afford to order a small selection, but it was more than enough to whet my appetite for more. I returned the next day, and the next, and the next furiously making notes on my laptop, but mostly just working through the collection to see what

was there. It was clear to me that these resources along with the materials at Kesey’s farm—were enough to form the foundation of my dissertation. I was beside myself with glee. It was also clear that if I wanted to get the most out of these collections I was going to have to come back the following year.

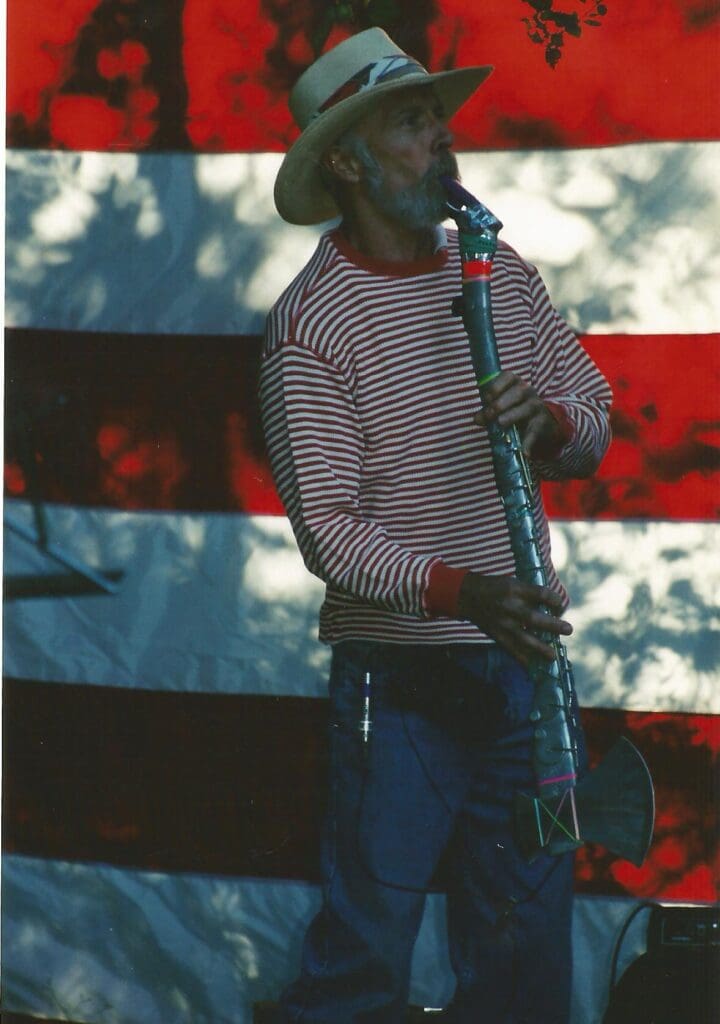

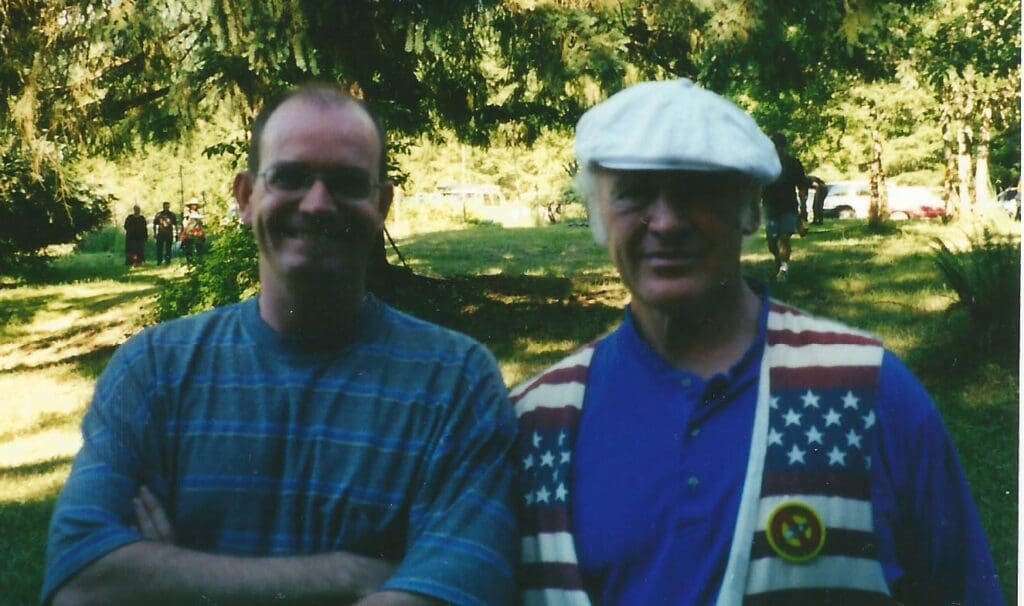

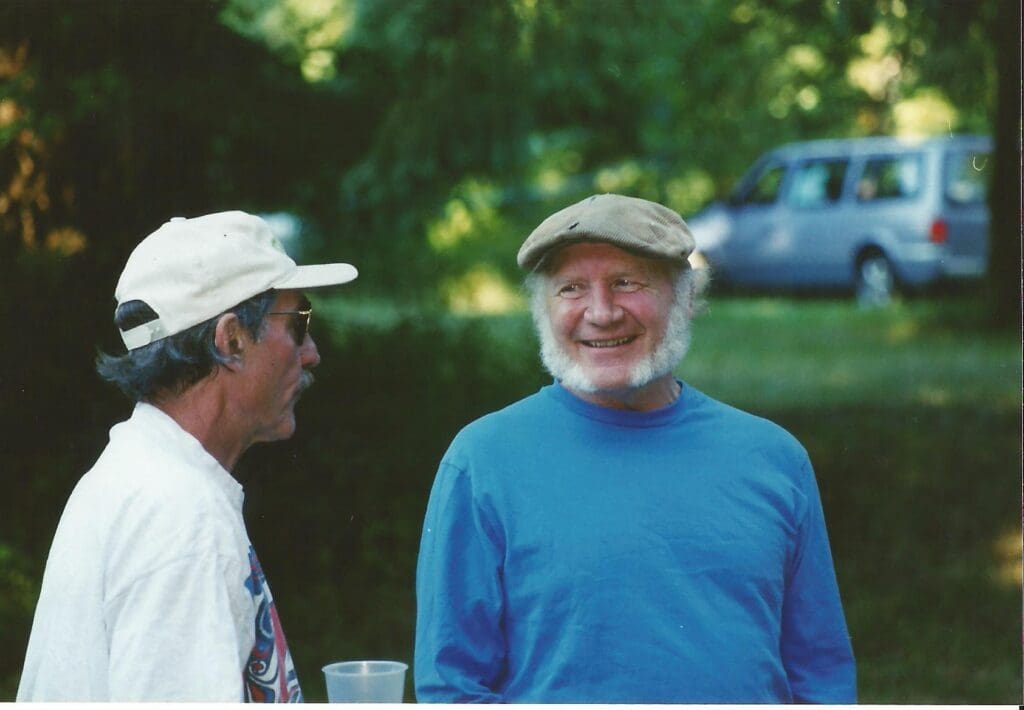

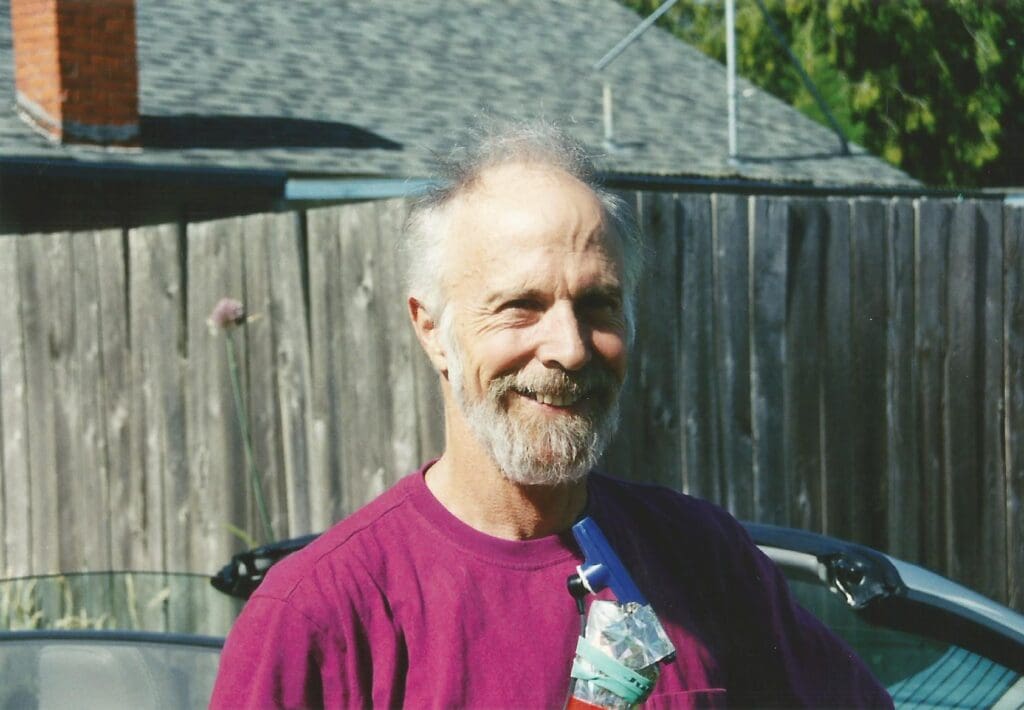

Babbs had invited me and the family to attend his July 4th party, which is the next time I encountered Kesey and the other Pranksters in person. Also in attendance were dozens of friends and family, including Sunshine Kesey, Kesey’s daughter with Mountain Girl; Chuck Kesey, Kesey’s younger brother, and a number of Babbs’ kids. A stage was set up next to the house to feature music and poetry through the afternoon. Picnic tables groaned under the weight of all the food and drink brought by guests. Children of various ages ran around the property, hiding behind trees, playing tag or ball. At one point Kesey organized a game of balloon stomp, something they used to play on Perry Lane, his old Stanford haunt. Participants each had a balloon attached to their ankles, which they had to try and protect, all the while trying to stomp on everybody else’s balloon. It was one hell of a scene. The highlight of the event was when Kesey and Chuck fired-off a small, but exceedingly loud brass cannon. The kids loved it.

This was a party, so I did not want to bother Kesey, Babbs or anyone else with questions about my project, but I did snatch a five minute conversation with Kesey in Babbs’ kitchen. He asked me how things were going, to which I gave an enthusiastic response. I asked him whether I could visit the farm again to do some more work in his personal archives. He was fine with the idea, and told me to just turn up at the farm and get on with it. I think he preferred that idea to me bothering him with questions or demands on his time. He was particularly busy with plans for the UK trip, which was less than a month away. I asked if I could photocopy materials from his archives and he happily agreed, even offering me the use of the photocopy in the IntrepidTrips office, telling me where the key was hidden in case nobody was around. I made a point of asking

him if there was anything he did not want me to photocopy, to which he replied that I could photocopy whatever I wanted. The following day I returned to the farm and settled into the archive to identify things to photocopy. This is what historians do on their research trips; they photocopy as much material as they can so that they can then work with the papers in the comforts of their home offices. Rather than use the IntrepidTrips photocopy machine, I took items from the archive to the local Kinkos where the machines were better and faster. I cannot recall exactly what I photocopied in all, but I do remember copying Kesey’s journal from the 1950s in its entirety. I was scheduled to leave a couple of days later. I spent another day in Kesey’s personal archives, and before I left, I asked him whether I could come back the following year to do more. He agreed without hesitation.

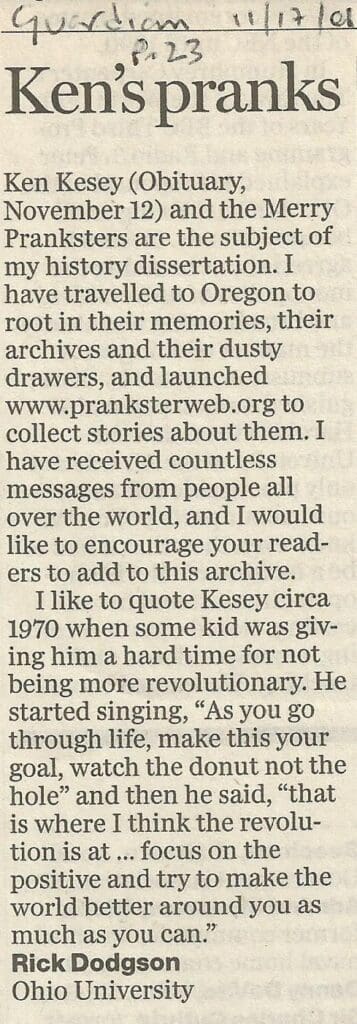

Over the course of the next twelve months, I started to collect all sorts of Kesey related material: books, magazines, newspapers, videos, CDs, photographs and more. One of my more unusual research tools was ebay. While I could rarely afford to bid on all the Kesey items, the site allowed me to identify the location of numerous forgotten interviews or articles in newspapers or various underground sixties publications. I also built a website—Pranksterweb.org—hoping to further my research by getting in touch with people outside of Kesey’s family or inner-circle. Through the website I was able to contact lots of people, including attendees at the Trips Festival that took place in San Francisco in early 1966; Hammond Guthrie and Jim Cushing, both Acid Test attendees; Lynn Rogers, a woman who encountered Kesey and friends down in Mexico over the summer of 1966, and Stewart Brand, a participant in some of the early Acid Tests and later publisher of the Whole Earth Catalogs.

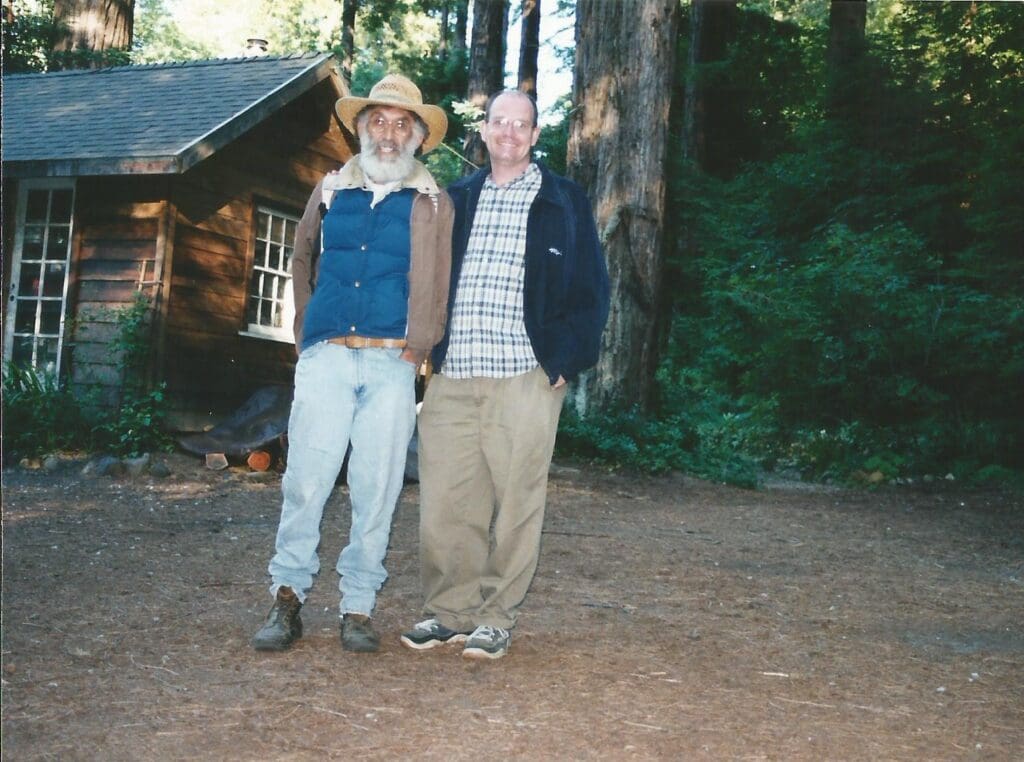

The following summer, 2000, I flew out to Oregon alone, leaving my wife to look after our newborn. Kesey and Babbs continued to be co-operative, even though I’m not sure that they remembered who I was at first. Kesey agreed to sign a form to allow me to conduct a Freedom of Information Act search to see if I could unearth his FBI records (which no longer exist, I discovered). Babbs declined a similar request. Kesey was particularly enthusiastic about my use of the internet in my work, seeing it as a way to approach this history from an interesting perspective. Babbs was kind enough to place a link to my Pranksterweb research site on the front page of the IntrepidTrips website. Endorsing my project in this way was very important. It added legitimacy to my work and helped open doors that might otherwise have remained closed. I asked Kesey if he would be willing to write a letter of introduction for me, for the same purpose. He suggested that I write it myself, and if he liked it, he would sign it. I came up with a couple of versions, one formal, the other more humorous. He chose to sign the latter. It read as follows: If you are reading this, then the gaze of Rick Dodgson has fallen upon you. For the past two summers Rick has made the trip out to Oregon to delve and probe into the Prankster archives in the misguided belief that they will allow him to make sense of the universe (and form the basis of his history dissertation). Despite this, as far as I can tell, he is not a complete idiot. I have given him free reign to rummage in my dusty drawers and I am helping him out as much as I am able in other ways. I would ask that you please do the same.

I spent two weeks out in Oregon on this particular trip, working mostly in Kesey’s personal archive and at the U of O. There I continued taking notes on the Kesey papers, but I also spent a good deal of my time straining my eyes on a microfilm machine, digging out old newspaper articles about the young Kesey, and discovering a treasure trove of his early journalistic efforts in the Daily Emerald, the U of O student newspaper. Babbs was kind enough to invite me again to his July 4 party, at which I was able to set up my first couple of interviews.

I started with Mountain Girl, who was incredibly gracious and forgiving of my nervousness. I also interviewed Anonymous, who was equally charming and helpful, and a couple of Kesey’s former professors at the U of O, Robert Clark and Horace C. Robinson. My one disappointment on this trip was that Kesey refused to sign a release form allowing me to quote from his papers.

He said he would have to see my work first.

The following summer, 2001, I arranged a four-week internship at the U of O, working on the Ken Kesey collection. As it turned out, they asked me to do very little. I organized the folders somewhat, helped locate Kesey’s Cuckoo’s Nest sketches for their inclusion in a new edition of the book, and I wrote a very short biography of Kesey for the library’s use, but other than that I spent day after day taking notes for my own research. While working through the papers, I also listened to the collection of audio cassettes that made up part of the holdings.

These tapes varied widely in quality and usefulness. Some were virtually incomprehensible, others simply full of music and inaudible conversation. Among the best was one of Kesey telling stories about his early days at Stanford. Another captured him recording his thoughts as the bulldozers moved in to demolish his house on Perry Lane in the summer of 1963. Listening to these recordings was time consuming, laborious work, but the occasional perfect quote or new piece of information made the effort worthwhile.

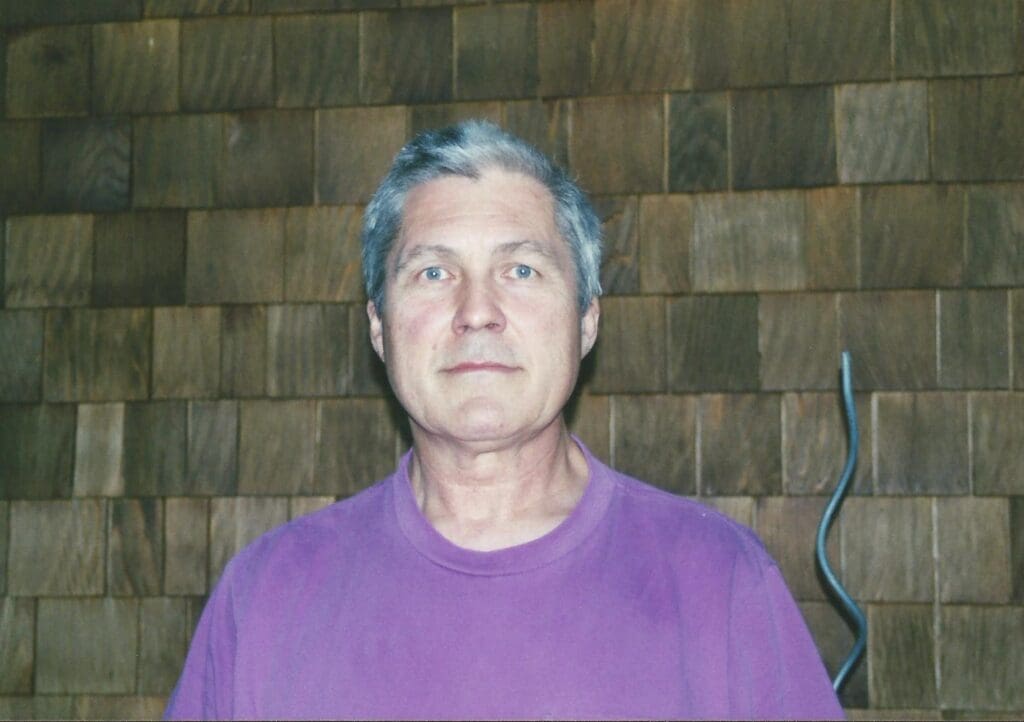

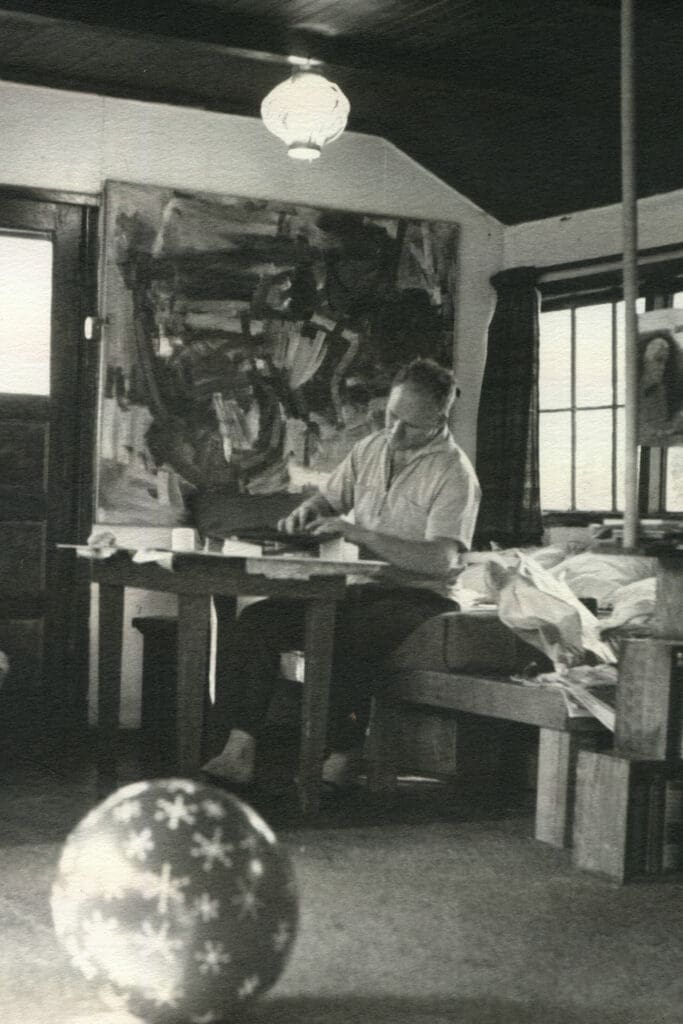

Venturing only occasionally outside of the library, I spent a day or two out at Kesey’s place completing my research in his personal archives, scanning some photos on a personal scanner that I had brought with me. By this time—my third visit—he remembered who I was and actually consented to a sit-down interview. To keep things interesting, we looked at some photos from his collection, using them to spark memories and stories. This approach worked, but only to a degree, as Kesey would begin talking about one photo, then get distracted by the next, never quite finishing one story until he was on to another. I regret not doing a better interview, but it was the best I could do under the circumstance.

When it came time for me to head home, I ventured out to the farm one last time to say my goodbyes. Kesey had always been somewhat personally distant over the course of our meetings, but on this occasion, he was warm and friendly. He asked about my family, and we talked a little about Faye’s health, which had been problematical. I had no idea he was sick himself. He told me that I should stay at the house next time I came out, rather than stay in a motel. He even gave me a quick man-hug as I went to leave. This was in early July, 2001. In early November, I found myself in New York, attending a conference at Hofstra University.

Naturally, the news media were still full of stories concerning the terrible events of September 11, but as I sat watching TV in my hotel room, I noticed a brief mention on the ticker tape scrolling across the bottom of the screen that Kesey had been hospitalized with liver problems. On the Saturday, November 10, I made my way into Manhattan to view what was left of the World Trade Center, at that point still a huge pile of smoking rubble. While I stood looking at the mess, and wondering what madness had befallen us, I received a phone call telling me that Kesey

had died. I would never claim to have been close to Kesey—I knew him through his papers, not personally—but I found myself shedding a tear when I got home and reported on his death on my website. I’m not sure whether I was crying over his passing, or because of the terrible events of that previous month. Either way, these were depressing days.

Over the course of the next couple of years, I continued my research up and down the West coast. I went back to Oregon again a couple of times, mostly to interview surviving Pranksters. I also spent lots of time in California speaking to characters from Kesey’s past: good people from the Perry Lane days, the La Honda period, the bus trip, the Acid tests and beyond. It was quite a journey, now that I think of it. I made some great finds, including the FBI agent who arrested the fugitive Kesey in October 1966, and the long lost “Who Cares Girl” from the Watts Acid Test. I spoke with Tom Wolfe by phone, and emailed with Owsley “Bear” Stanley, the “Acid King” of the Haight Ashbury. I did yoga in Venice Beach with Denise Kaufman, former Acid Test Prankster turned celebrated yogi; and had lunch with Hog Farmer Wavy Gravy in Berkeley (he insisted on the pork). It was not all fun. At least two people cried during their interviews. A few people did not want to talk to me, and a couple did so somewhat reluctantly.

Many of the actors in this book are still with us. This history is still alive for them, and it is a difficult history for some. Not everything is merry about this story. Everyone I met, though, was gracious and helpful. I would like to thank them for sharing their lives and thoughts with me.

This book covers the early chapters of Kesey’s life, at least as I know it.

The Mavericks of La Honda (Sample Chapter)

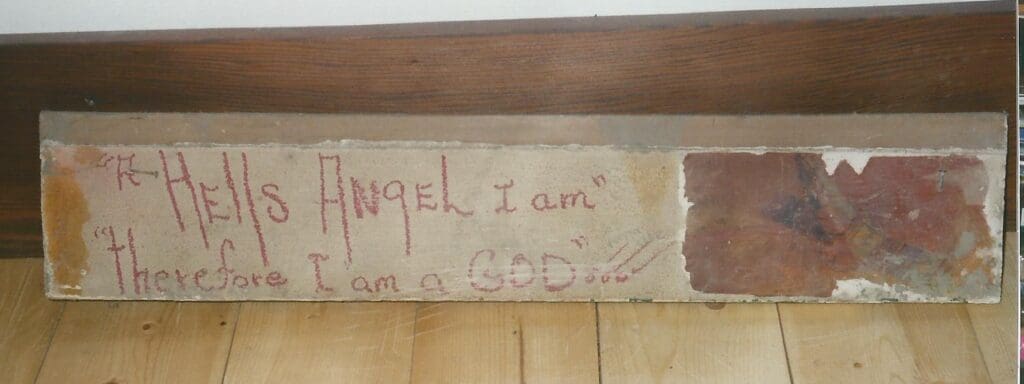

The Kesey’s new home in La Honda was only fifteen miles or so from Perry Lane, but the two places could not have been more different. La Honda was a fairly isolated village community, nestled on the westward slopes of the Redwood hills that separated Palo Alto from the Pacific Ocean. The location looked and felt more like Oregon than California, possessed of a rainy climate and an earthy character that even Hank Stamper would have found familiar. In the mid-nineteenth century the place was not much more than a few lumber mills and a stagecoach stop, but it grew as its industry expanded. A schoolhouse was built in 1870 and local legend had it that in 1877 some members of the infamous Younger Brothers gang settled in the area and built the old Pioneer Mercantile Store in what was then the center of La Honda. By the turn of the century the commercial and residential heart of La Honda had moved about three quarters of a mile up the road from the Pioneer Mercantile Store to its present day location. It had a saloon, a dance hall, a new school house, a post office, a hotel, a blacksmith and a burgeoning tourist industry that attracted hundreds of visitors from San Francisco and elsewhere on the peninsula. To meet the growing demand, La Honda soon boasted four hotels and seven bars, one of which was famous for hosting frog shooting competitions and musical entertainment by a group possessed of the unlikely name of the Tapioca Band. On summer weekends up to three hundred campers would pitch their tents all over La Honda, especially down by La Honda Creek which was renowned for its bountiful supply of trout.

La Honda’s heyday did not last long. When its virgin timber ran out in 1910, its logging industry rapidly declined. And with the advent of the automobile, vacationers from the city started venturing further south to Santa Cruz or Monterey. The final nail in the coffin came with the stock market crash of 1929, which collapsed real estate values and put an end to any large scale residential development in the area for the next thirty five years. Its economy in tatters, La Honda become something of a forgotten backwater, home to mavericks and a few old-timers; all possessed of “a spark of pioneer in their blood that makes them want to venture out where conformity has never yet been witnessed,” as one newspaper reported.[1] By the early 1960s, La Honda was starting to recover, in part because it was turning into the peninsula’s version of Big Sur; increasingly home to all manner of artists, writers, naturists and people who just wanted to get away from it all. Robert Stone described it as a place that “had the quality of a raw Northwestern logging town, transported to suburban San Francisco.”[2] No wonder Kesey loved it. In August, 1963, he, Faye and the kids, including the new one, Jed, became the latest and most famous mavericks on La Honda’s block.

[1] Tom Stockley, "La Honda: The Peninsula's Maverick Community," The Advance-Star and Green Sheet, June 19 1966.

[2] Stone, "The Prince of Possibility," 70.

Media