Musical History

My Life in Music

Music is like oxygen to me; it runs in my blood and feeds my brain. It has been a constant companion in my life since as long as I can remember. There is still not a day that goes by that I do not listen to music, pick up my guitar or work on writing songs. My own music is a true reflection of who I am, where I come from, and how I see the world. I’m much more of a musician than I am a writer or an academic, in fact, I’d rather play music with people than talk most of the time (unless we’re talking about music). I came of age in the 1970s, in an era when rock music was still a revolutionary force, still outside of the mainstream, still a medium for the countercultural idealism of the sixties. At least, that’s what it felt like to the young me. As a result, music has always been more than just a form of entertainment, it must really “say something” to get my full attention. I like “Louie, Louie” as much as the next man, but I’m more drawn to a weird or thoughtful lyric, or some deep philosophical meanderings about human nature.

I was born too late (1961) to really appreciate the Beatles, but they were still a huge influence. Some of the first albums I bought were solo Beatle albums, like Band on the Run (1973) by Paul McCartney and Wings, or Imagine (1971) by John Lennon. I appreciated McCartney’s brilliant pop songwriting, but it was Lennon’s raw idealism that really appealed. “Happy Xmas (War is Over)”, by Lennon and Yoko Ono, was also an important moment for me. Lennon remains one of my heroes. Yoko too, actually. And Paul, of course. The Beatles were ever-present when I was growing up, but my introduction to other music came from watching Top of the Pops every week on BBC TV, and listening to the Radio 1 chart countdown show every Sunday evening. At the age of 12 (around 1973) I acquired my first few pop singles by collecting tokens off packets of crisps—Quavers, I recall, or was it Hula Hoops?—and sending them off for free music. Six tokens got you a free top ten hit. Some of the singles I acquired were pretty cool in retrospect—stuff like Wizzard’s “See My Baby Jive” or Suzi Quattro’s “Can the Can”—but the young me was equally excited to receive such classic chart toppers as the “Monster Mash” by Bobby “Boris” Pickett and the Crypt Kickers, or “Eye Level” by the Simon Park Orchestra (which was the theme music to a popular TV show at the time).

I flirted with the British Glam music of the early 1970s—Slade, Sweet, T-Rex, Bowie—but I wasn’t fully convinced that glitter was for me. Eventually I became a huge David Bowie fan, but I didn’t really appreciate his brilliance at the time. By the mid-1970s, my tastes had started to become a little more focused. I recall being mesmerized watching Queen perform “Seven Seas of Rhye” and “Killer Queen” on Top of the Pops in 1974, and the Sheer Heart Attack album was one of my first moves away from the Beatles. I wore out my “Bohemian Rhapsody” 45—and my parents’ patience—by playing it over and over again on my little stereo. By this point I had realized the difference between (throwaway) pop music and (meaningful) rock music, and my heart and soul were committed to the latter.

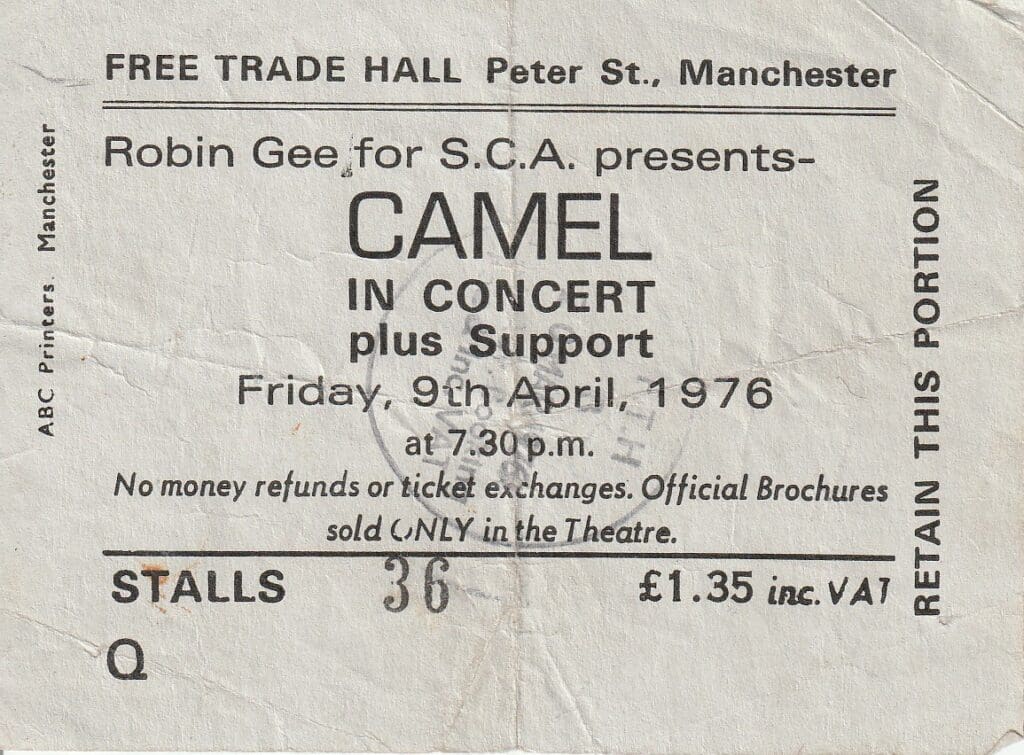

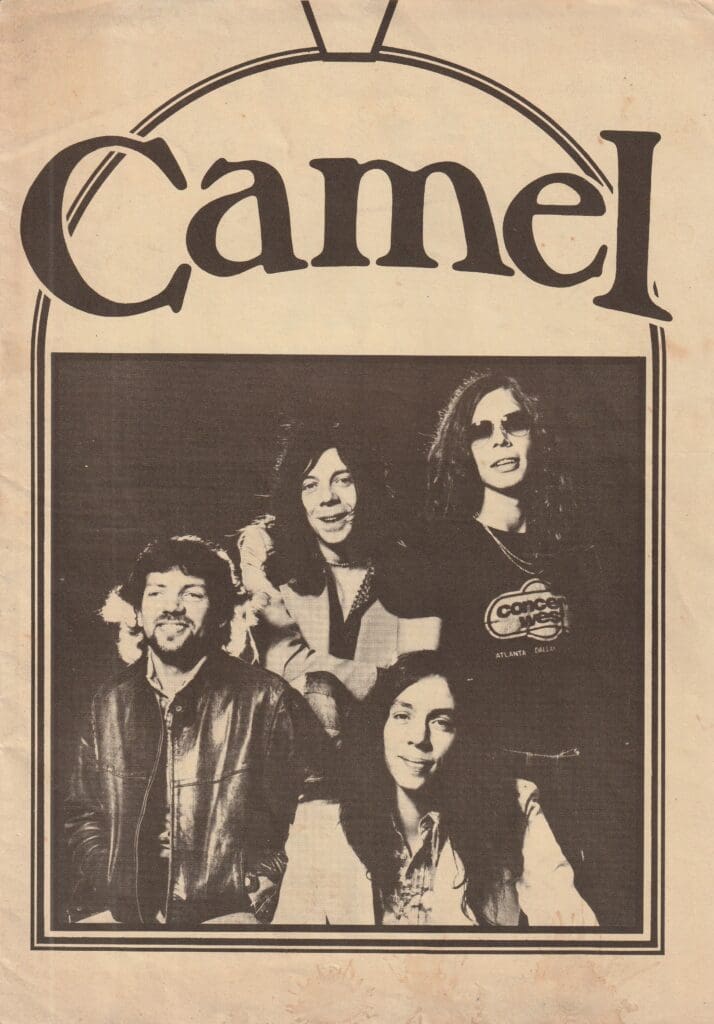

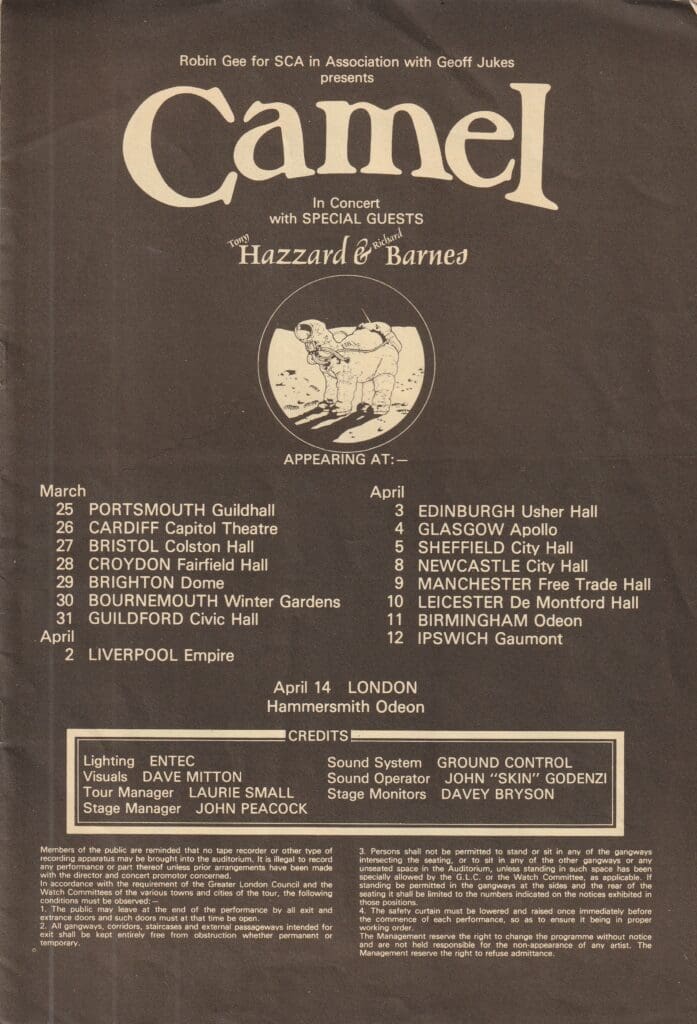

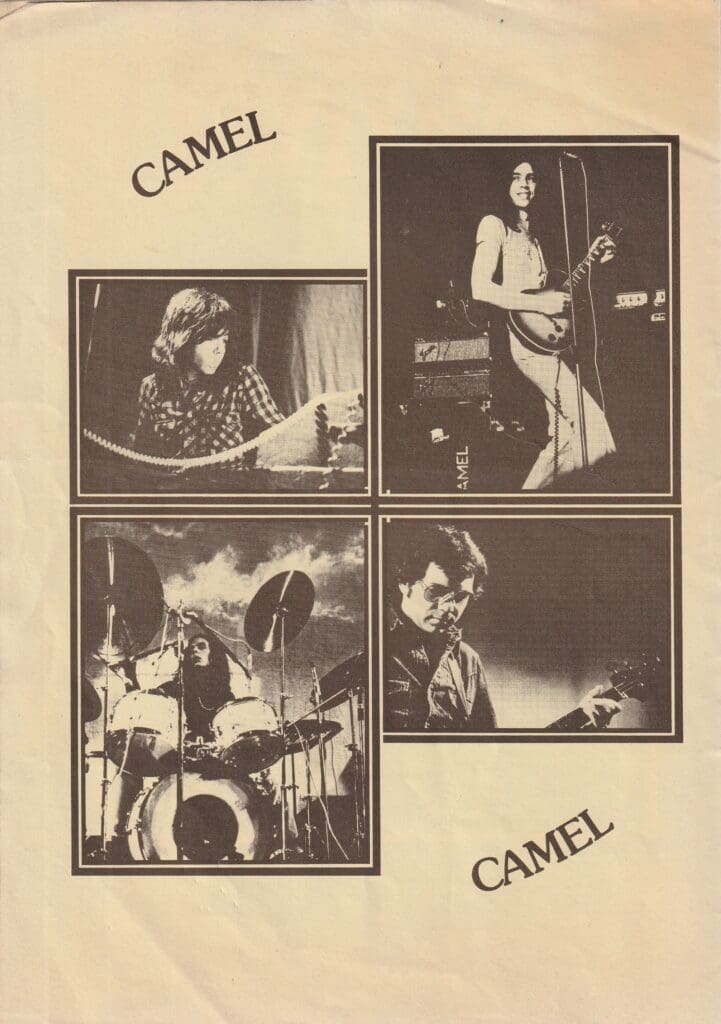

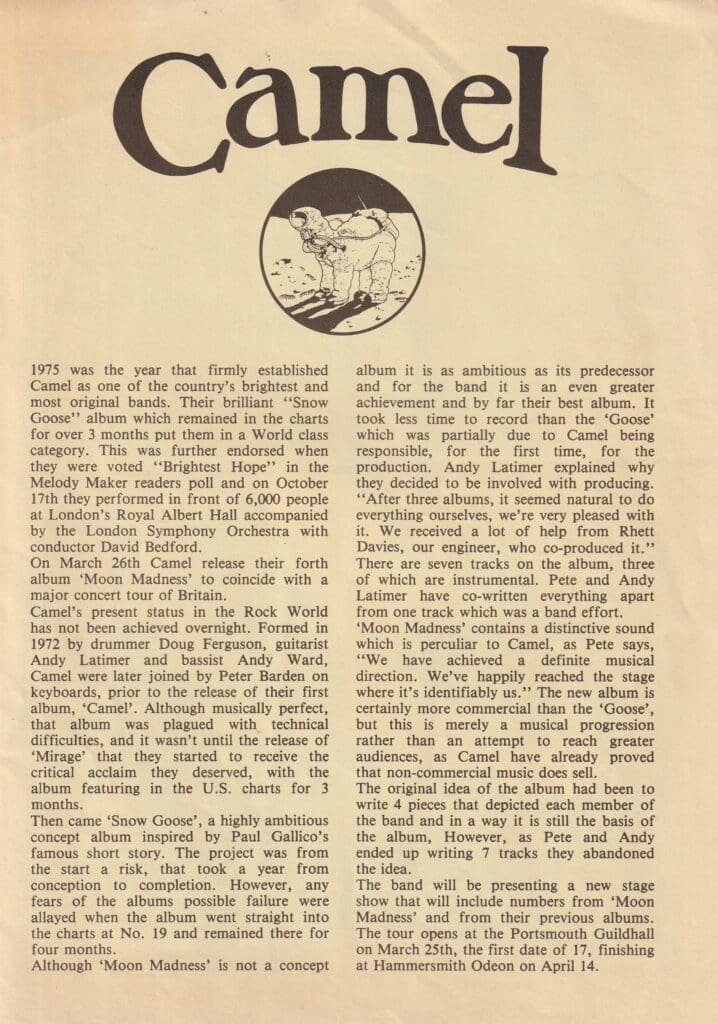

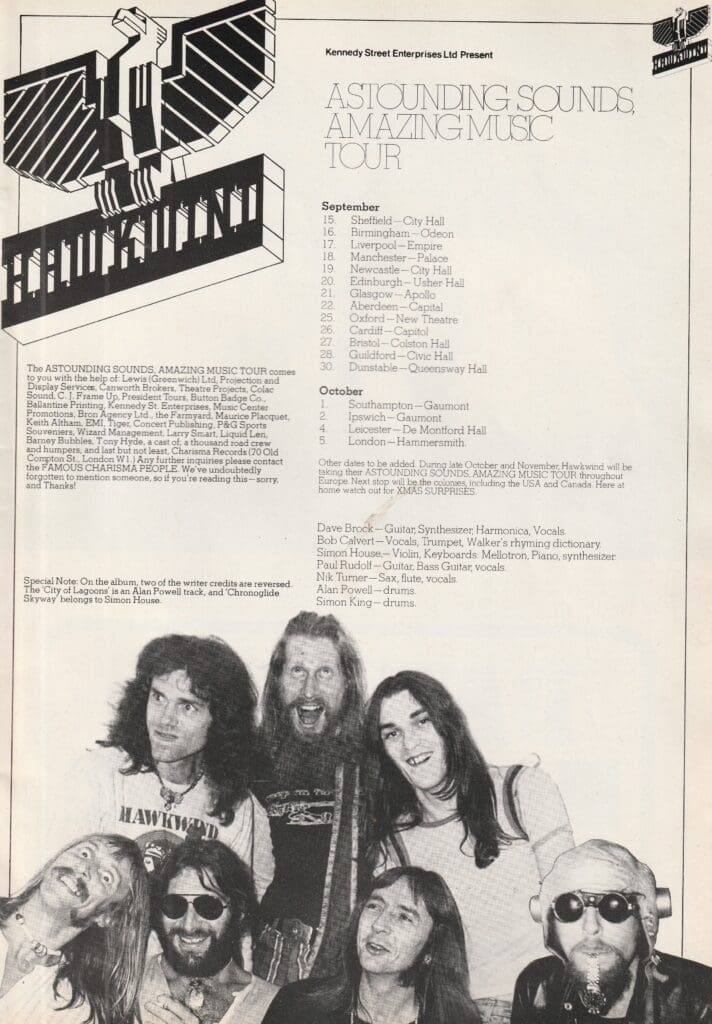

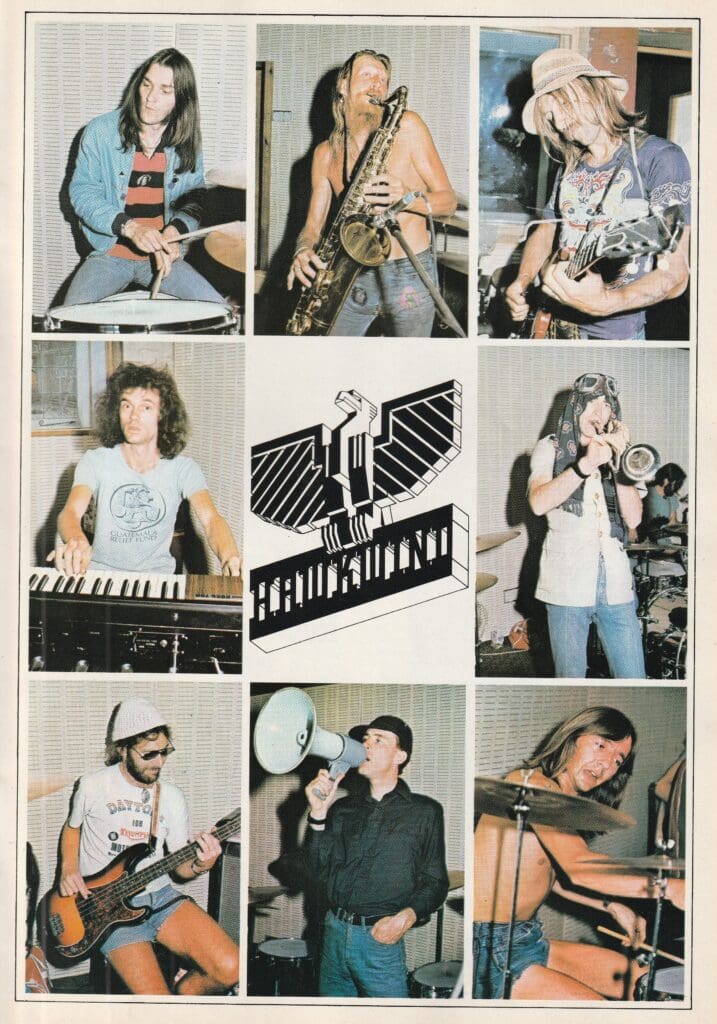

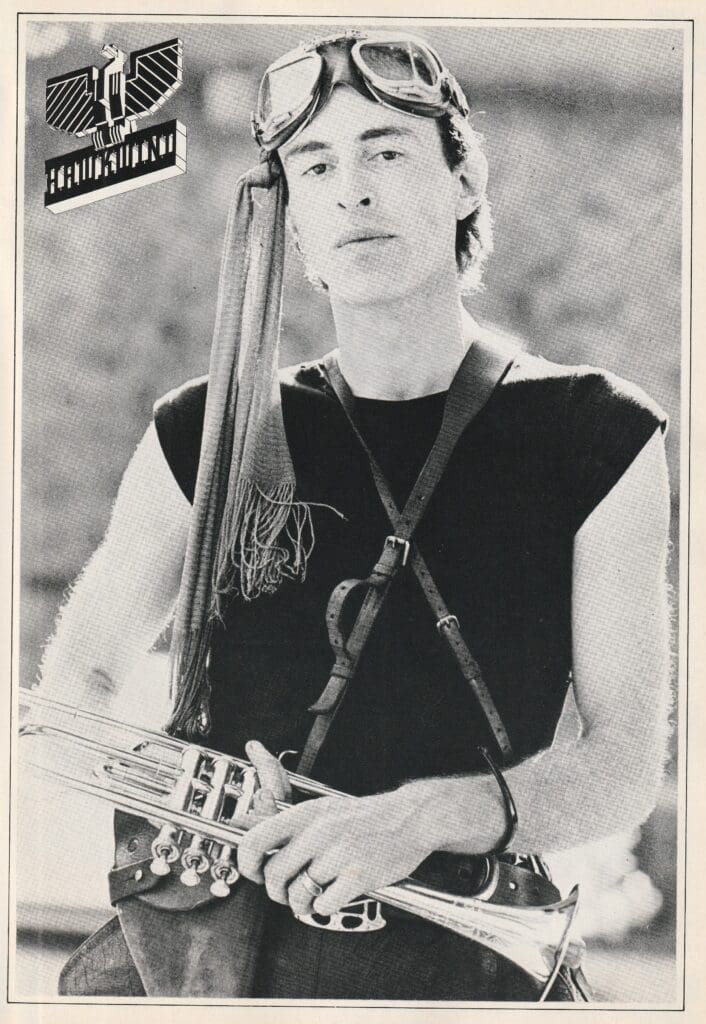

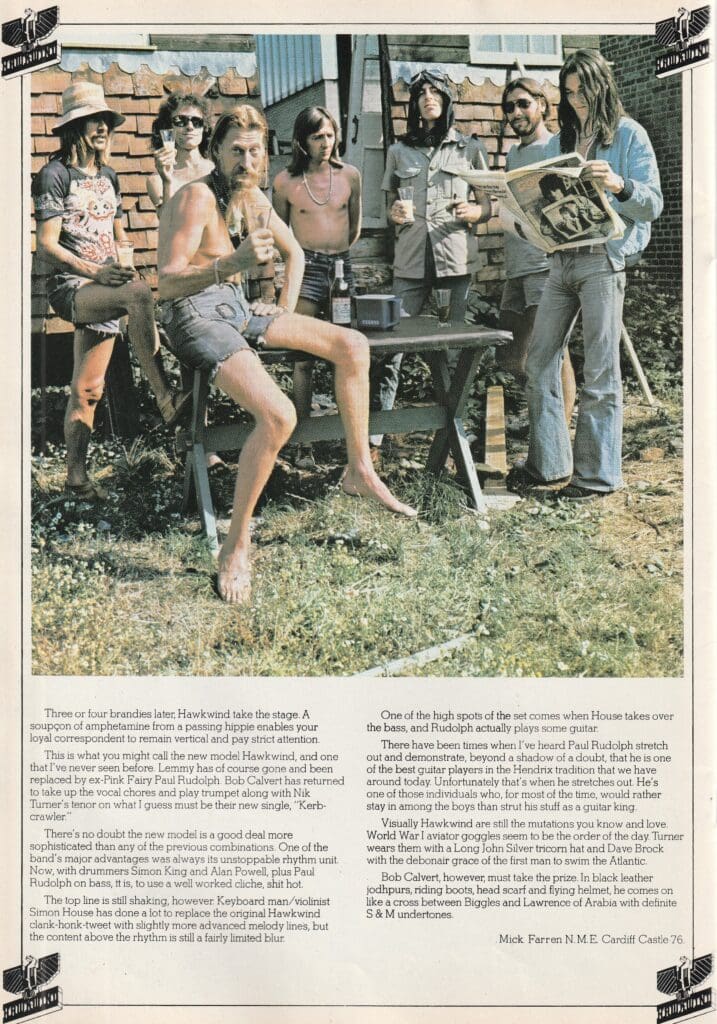

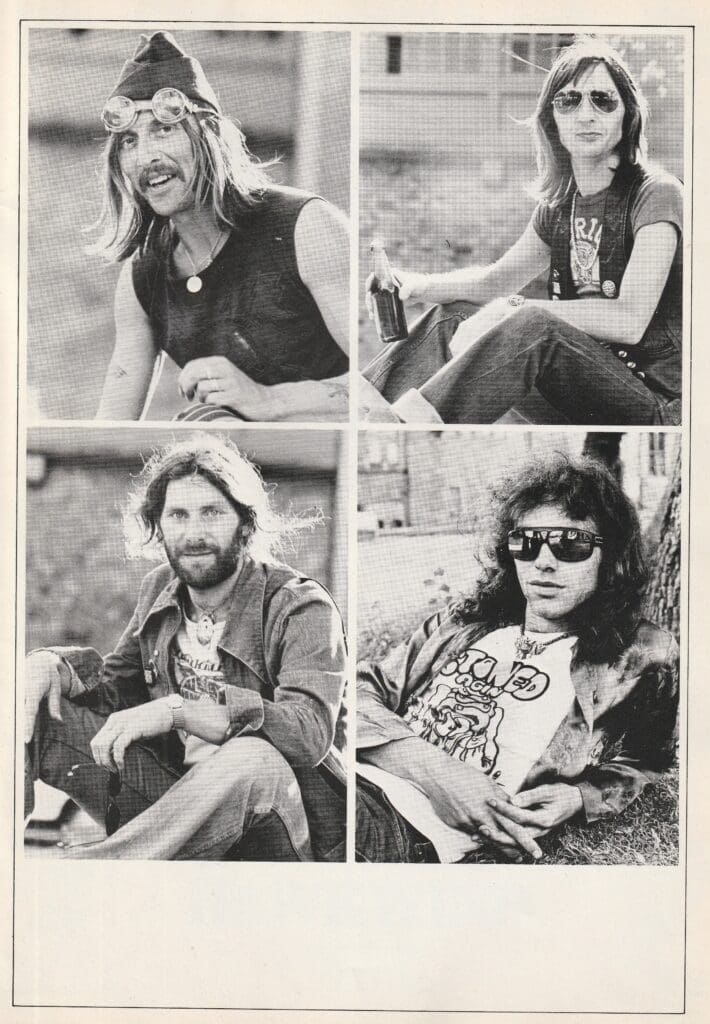

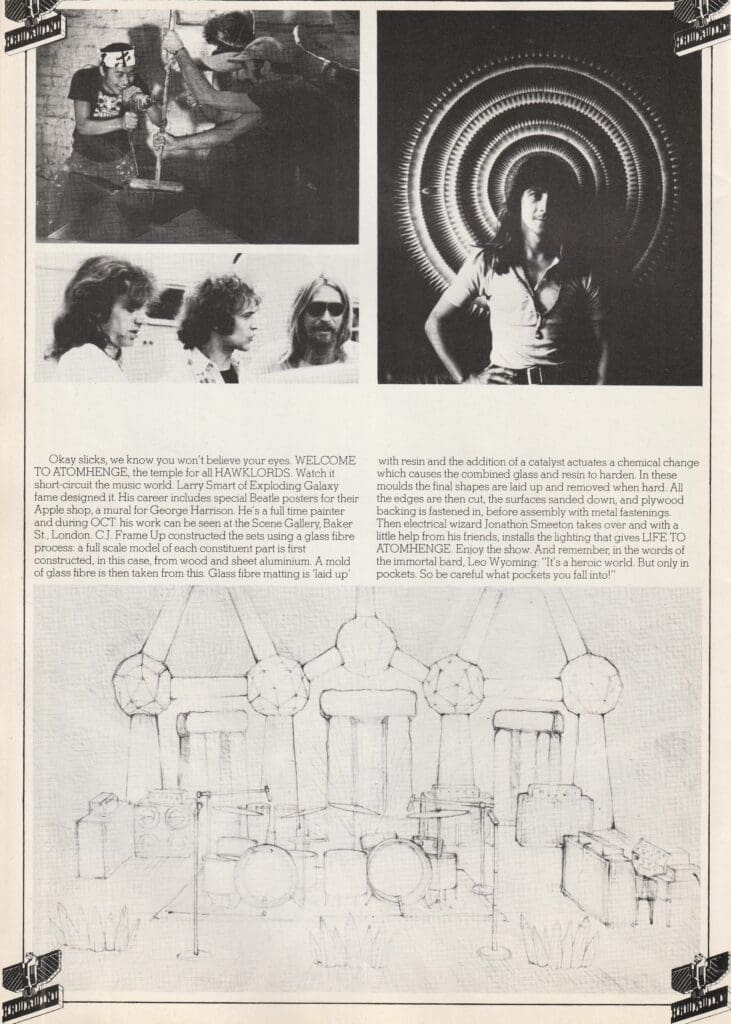

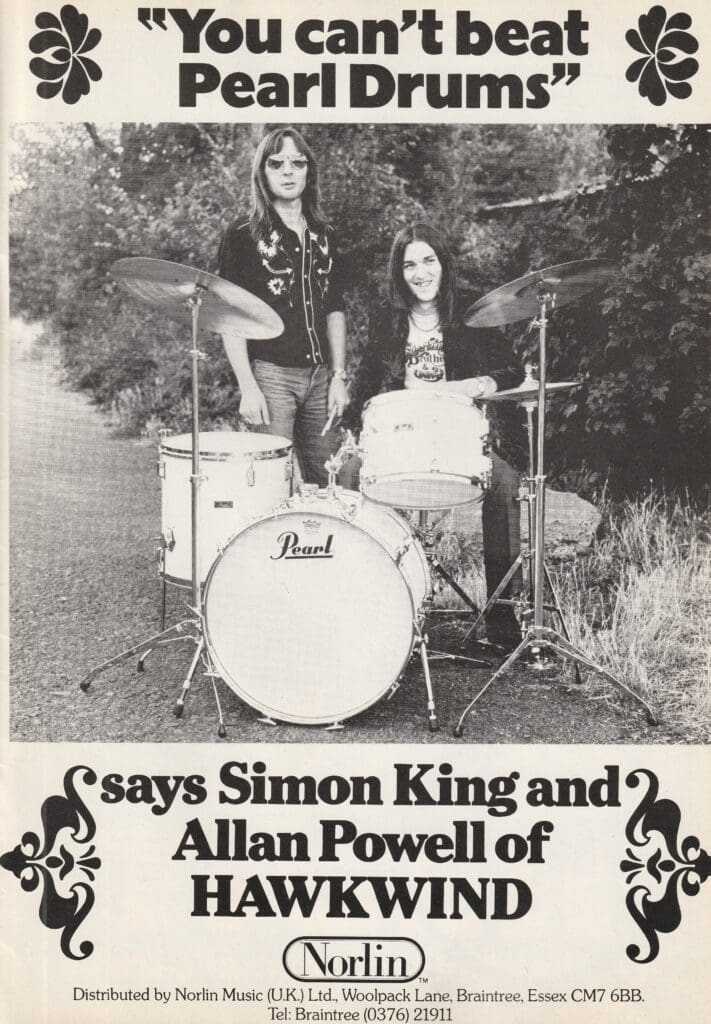

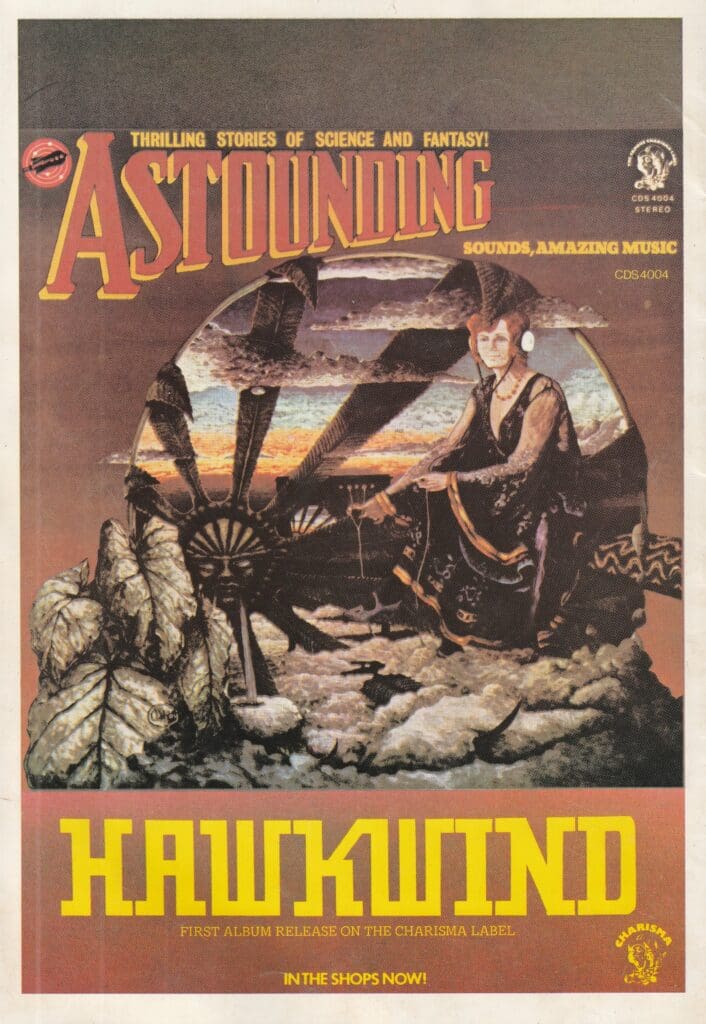

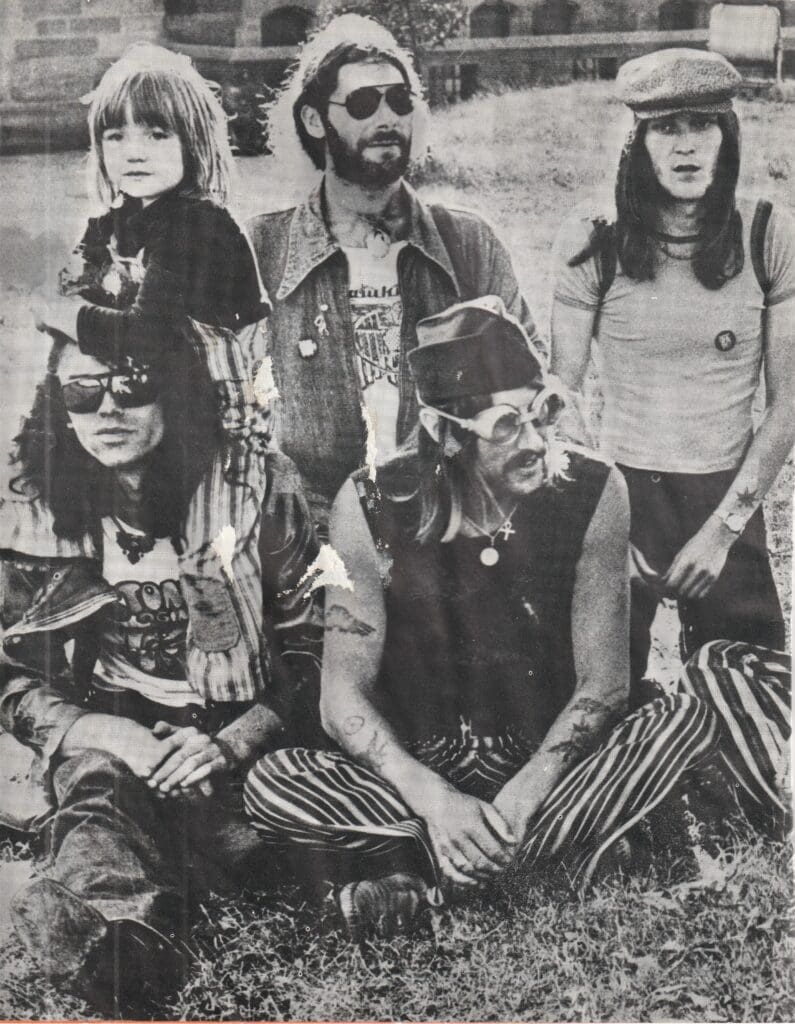

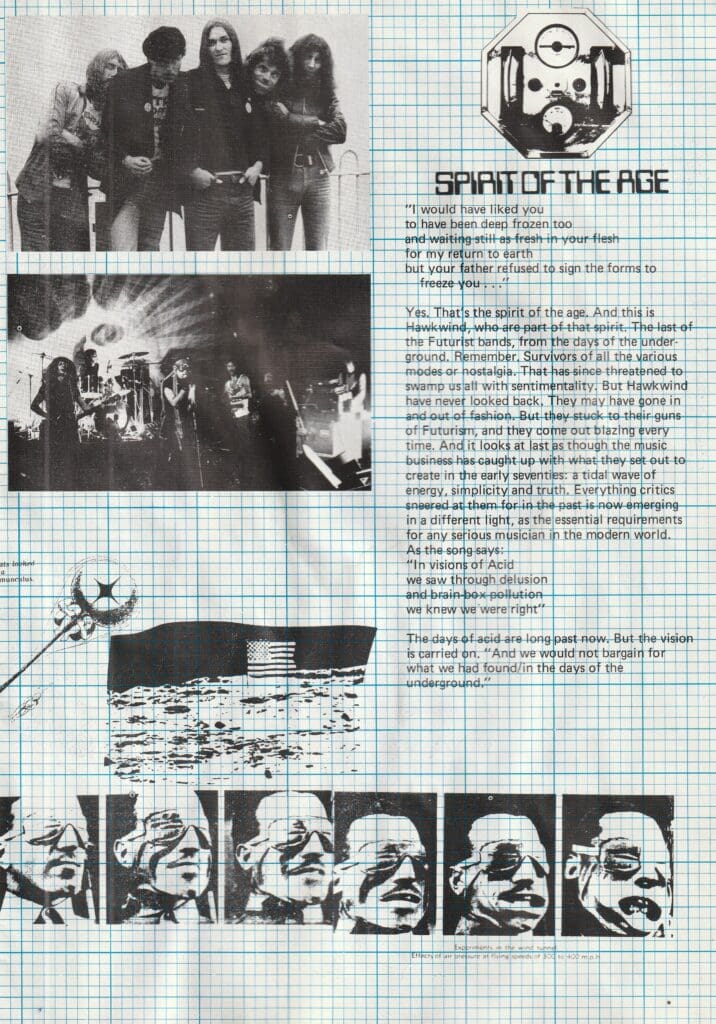

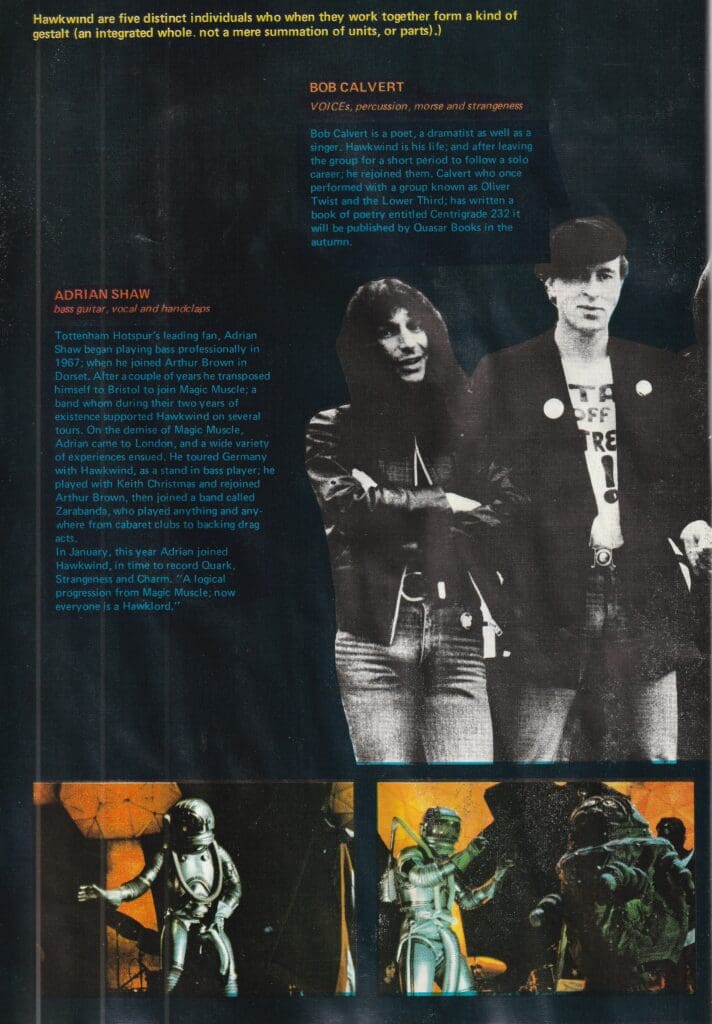

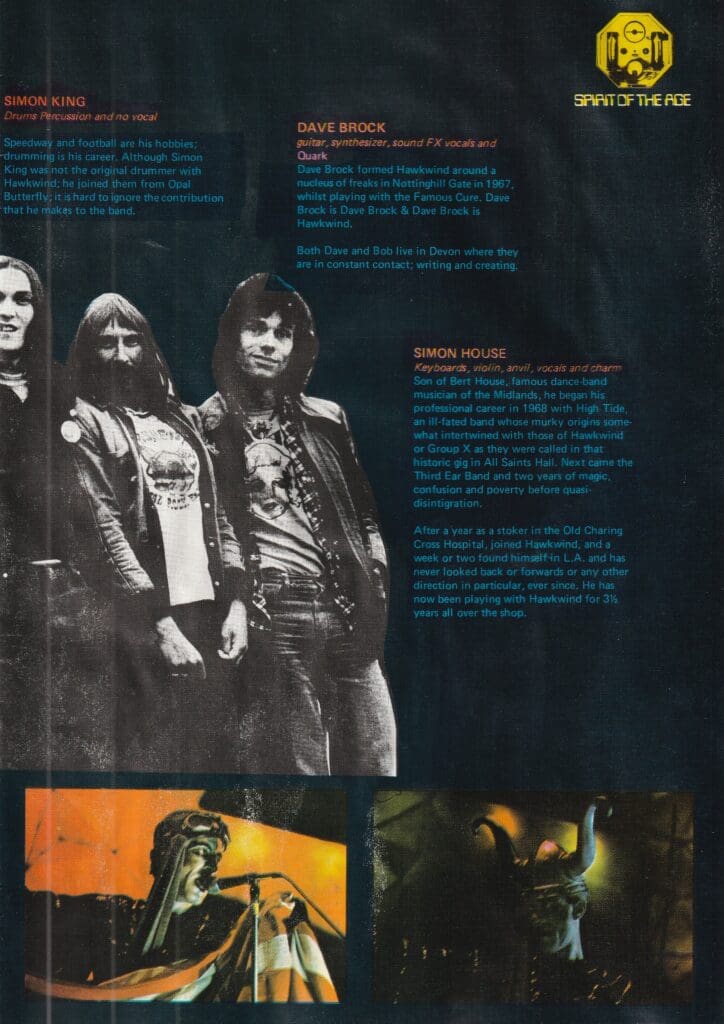

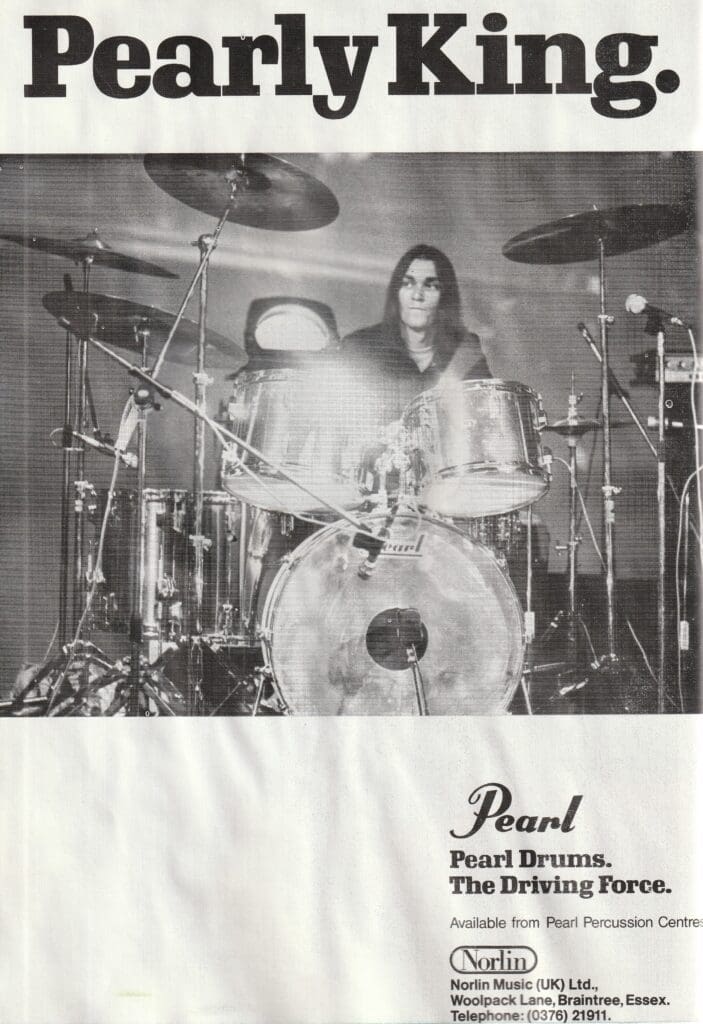

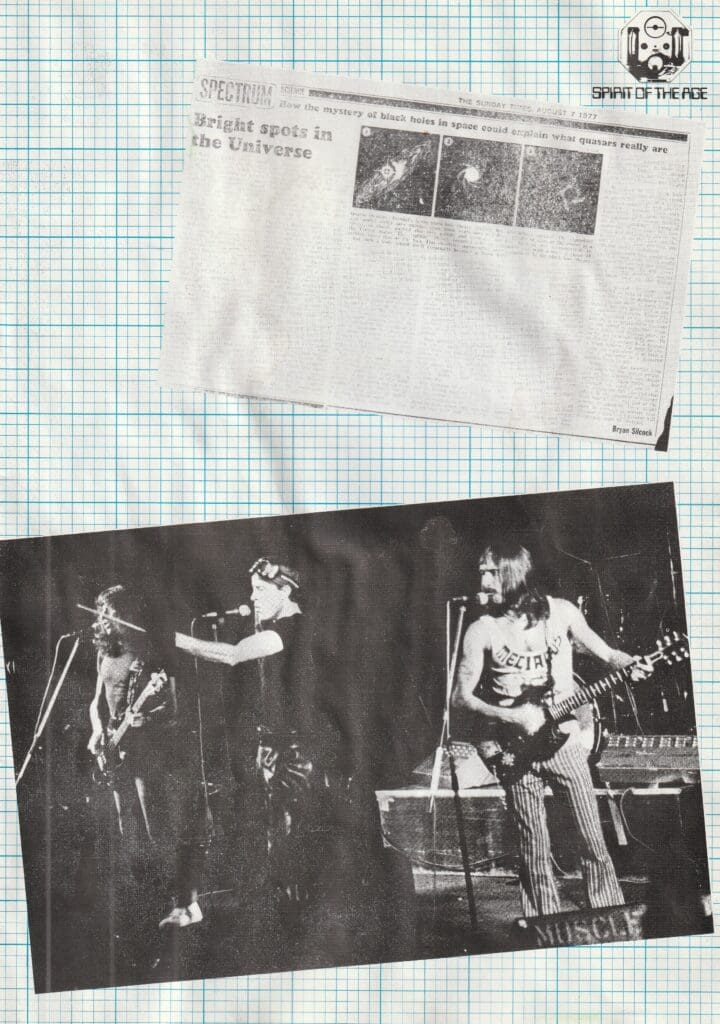

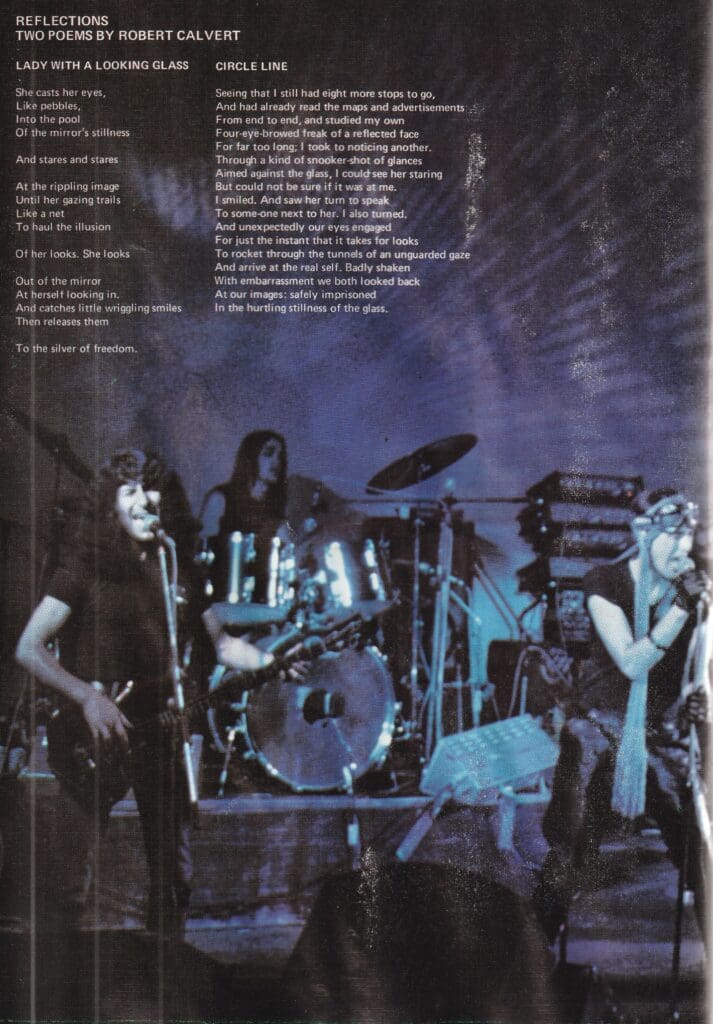

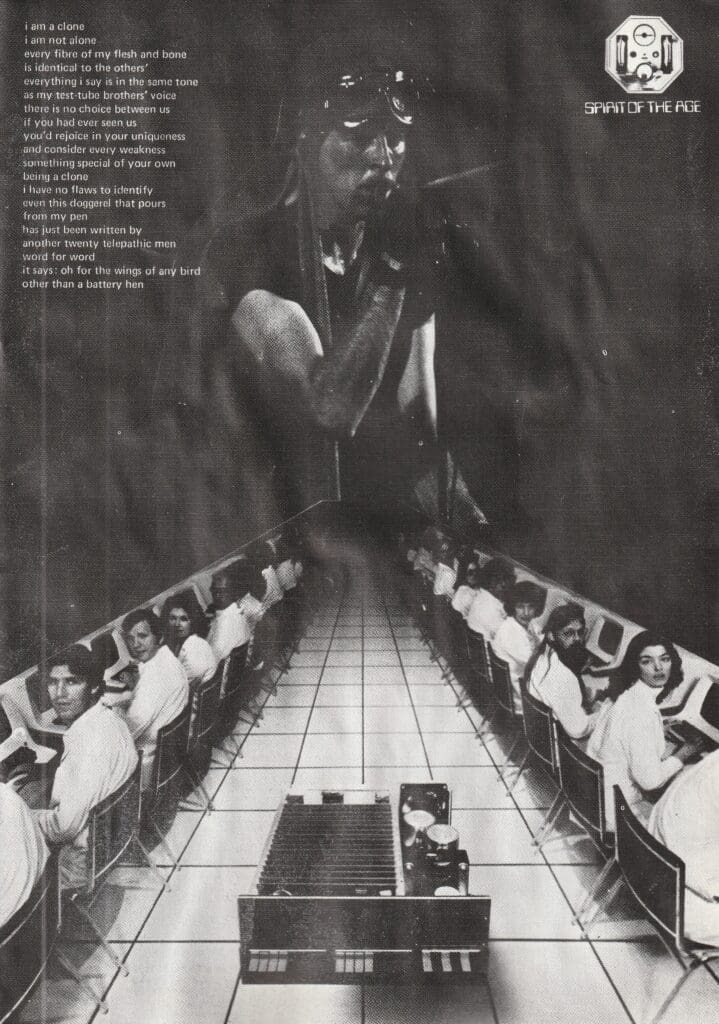

I discovered Queen on my own, but thereafter my musical education came courtesy of a school friend called Stuart “Gilly” McGill, whose older sister was a full-on afghan-wearing, patchouli-smelling, dope-smoking, commune dwelling, English hippie who fed us a wide selection of the coolest music around. Thus began my introduction to British progressive music of all stripes, from the epic psychedelia of Pink Floyd, to the very English Canterbury scene (Soft Machine, Caravan, Gong), to the outer reaches of Space Rock with Hawkwind, and the Art Rock of Genesis, Camel and Van Der Graf Generator. I was never much one for the Blues, but I do remember having a few Zeppelin and Sabbath records, as well live albums by the Climax Blues Band and Wishbone Ash. I also had a strange selection of American rock, including LPs by Bob Seger and the Silver Bullet Band, Steely Dan, Blue Oyster Cult, even Lynard Skynard Live. Strange to find such a disparate collection of music in my teenage hands, but I was just like a sponge, soaking it all up, buying what I could find on sale at my local Woolworths. My only ambition at the time was to own more records than Gilly. My first live concert was going to see Camel in 1976 at the Manchester Free Trade Hall. This was a famous old venue, built for public meetings and concerts and paid for by public subscription. Winston Churchill once spoke there, as did Benjamin Disraeli, and Charles Dickens once acted on its stage. By the 1960s it had become one of Manchester’s best concert venues. Dylan was famously labeled “Judas” by an angry folkie during his May 1966 oncert at the venue, but by the I970s, the place was better known for its progressive rock concerts. Pink Floyd had played there a bunch, and Genesis played there on their famous 1973 Foxtrot tour. I wish I’d been there for that one, but by the time I got into Genesis, the “Lamb Lies Down on Broadway” had come out and Peter Gabriel had left the band.

Camel were promoting their Moonmadness album, their fourth. I was lucky to catch them with their original line-up of Andy Latimer, Doug Ferguson, Andy Ward and Peter Barden. Tickets cost £1.65 (about $2.50) including VAT, but excluding all the bullshit fees you have to pay today. The gig was on Friday, April 9, my mother’s 41st birthday. I was not yet 15. We lived about 30 minutes outside of Manchester, in a place called Golborne, Lancashire. I seem to recall my mum dropping me off and picking me up after the show. She was nervous as hell that I was going to be corrupted by the throngs of lanky haired men in long grey coats and thick glasses lining up for tickets. She told me that if she caught me smoking pot, she would turn me in to the police. I can’t remember much about the actual show, other than wishing that I could play guitar like Andy Latimer. I do remember feeling that I’d found my place in the cosmos, here in the world of rock music and the aromatic counterculture that went with it. Sorry mum. Thanks Gilly!

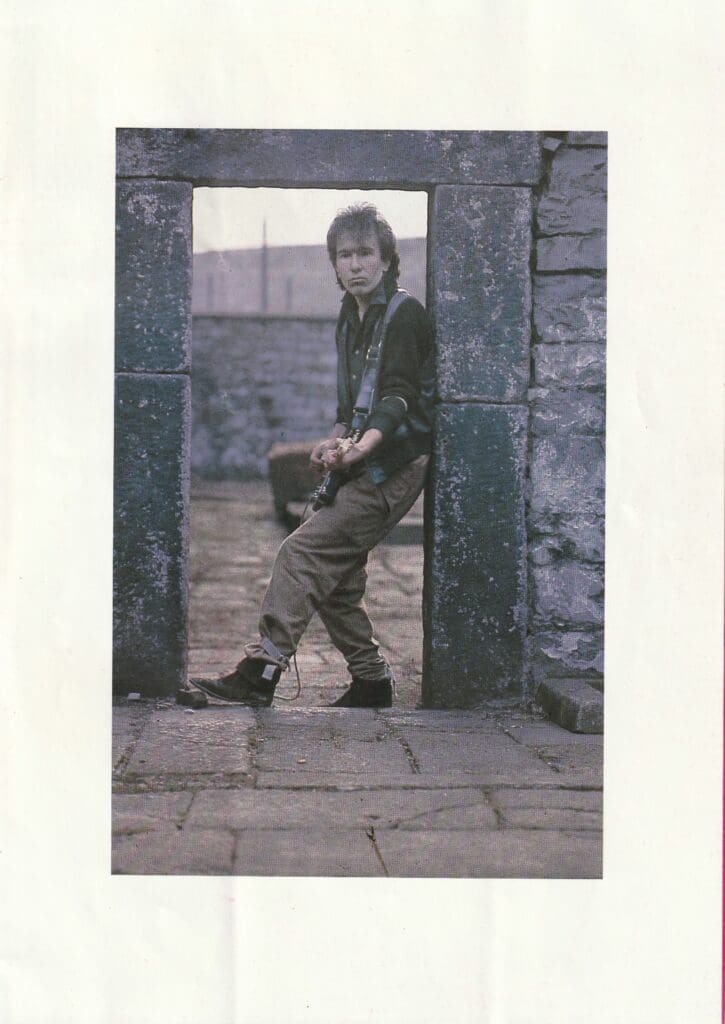

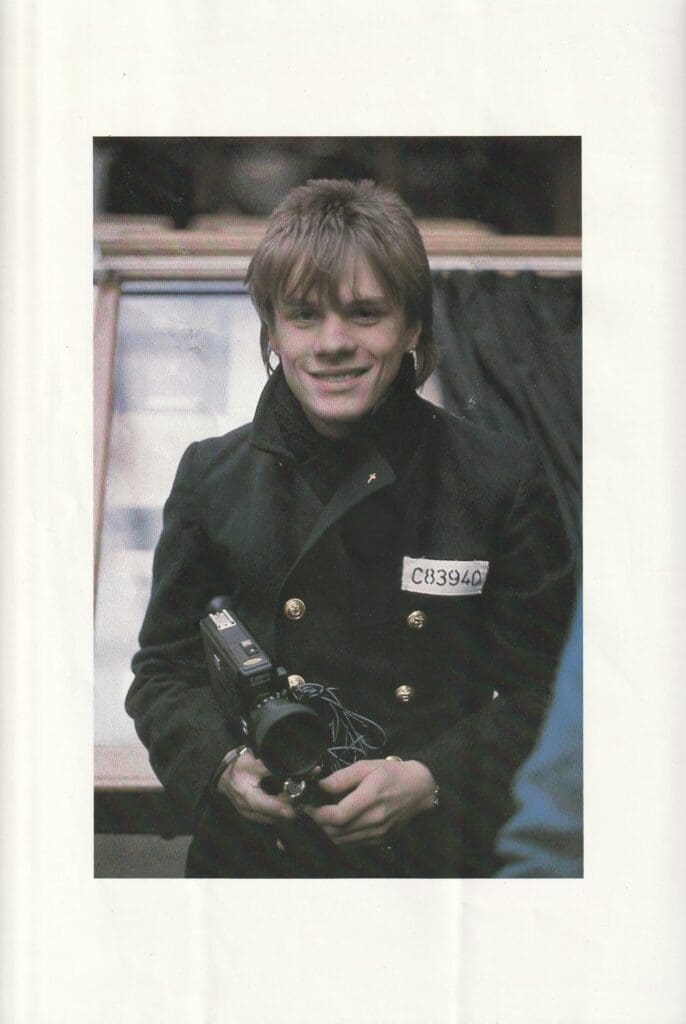

Actually, at that stage I was still pretty clueless about most things. For example, I had no money to buy merchandise at the show, so I wrote to Camel’s record company and asked if they had any posters leftover from the last tour, and if so, could I have one of them for free. They politely declined. Anxious to get closer to the action, I also asked for a photographer pass for Camel’s next tour (Rain Dances). They said yes, but I couldn’t take them up on it because I didn’t have a camera.

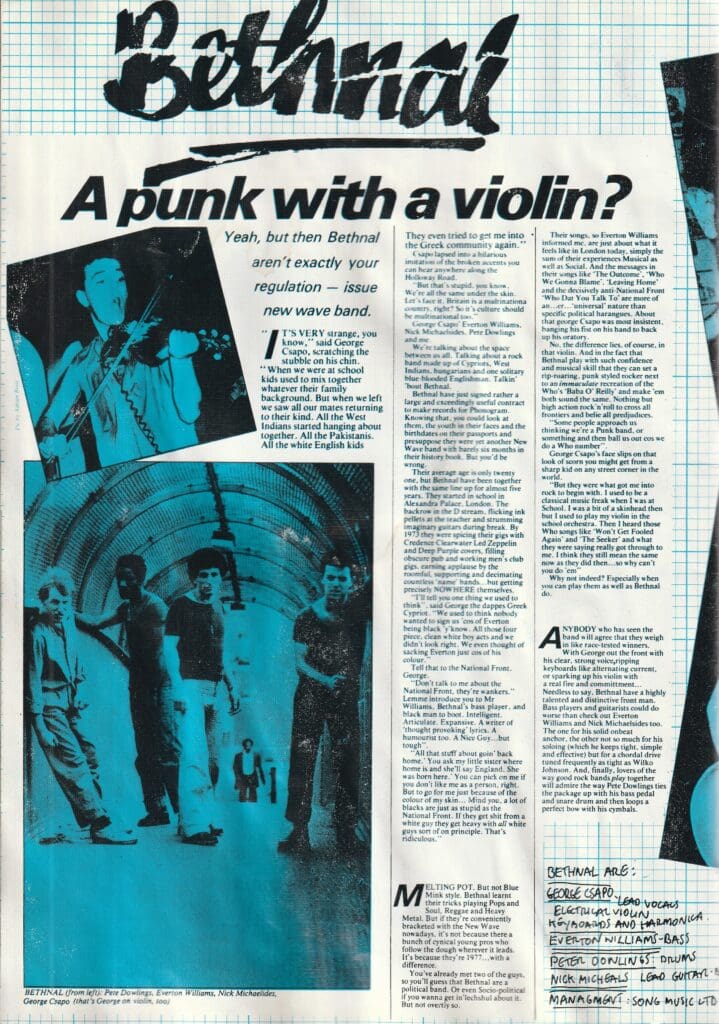

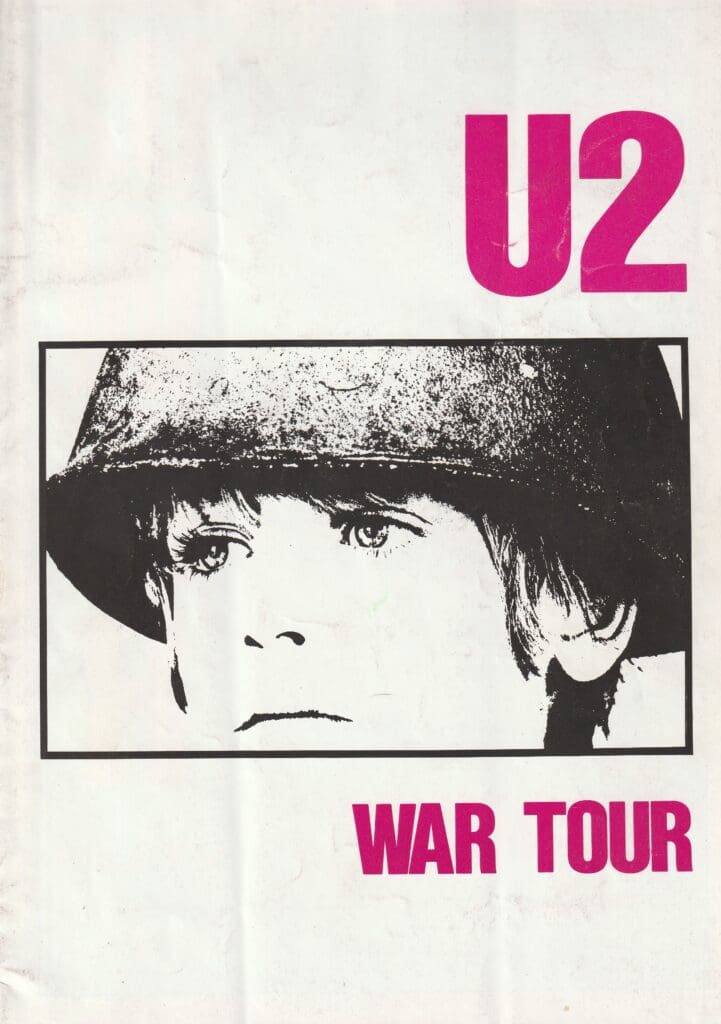

Little did I know that just as I was getting into progressive rock, it had less than two months to live. On June 4, 1976, the Sex Pistols would famously play their first show in Manchester at the Lesser Free Trade Hall, a smaller room next to the concert venue where I had seen Camel not two months earlier. Camel are sadly forgotten by most, but the Pistols gig (and the one that followed six weeks later) is remembered as one of the most important moments in rock history, credited with sowing the seeds of punk in Manchester and leading to the creation of numerous memorable bands—The Buzzcocks, Magazine, Joy Division, New Order, the Fall, A Certain Ratio, Simply Red, the Smiths—as well as the creation of Factory Records, and by extension, the Hacienda club. Sadly, I was not there. I read about it later in the New Musical Express. I loved punk when it came out—I remember buying the Damned’s first album—but I was always more of a hippie punk than the real thing.

My favorite band of this period was called Here and Now, an anarchic offshoot of Gong, who occupied the same punky hippy space as I did. They played for free and drove around in converted buses like latter day Punky Merry Pranksters. I thought they were great! I must have seen them a dozen times, including at Eric’s in Liverpool, at a legendary Deeply Vale festival, and most often in an unlikely sports center venue in Westhoughton, close to where I lived in Leigh, Lancashire. As a teenager, I once called them up—I can’t remember how I got their number—and arranged a gig for them at a punk club in nearby Wigan, Lancashire. I remember that after their sound check someone, Keith da Missile Bass I think, invited me on the bus to “hang out”, but I told him that I had to go home for my tea. Like I said: clueless. I never saw Here and Now with Daevid Allen, but their Planet Gong album remains one of my favorites to this day.

It's around this time that I started playing guitar and writing songs. I have a “unique style,” which is another way of saying that I’m self-taught and lost when it comes to musical theory or proper technique. The first song that I learnt was “House of the Rising Sun.” It was also the last. After I’d mastered a few chords, all I was interested in was coming up with my own songs. At first, they sounded like bad Lennon rip-offs, or Hawkwind B-sides, or, later, pale tributes to Echo and the Bunnymen, one of my favorite bands of the 1980s, but I eventually found a style and a voice that I could call my own. I still don’t know any songs by other artists. This makes me the worst person to invite to a party or a beach fire sing-a-long, but as a songwriter I find it liberating, free to come up with riffs or chords or melodies without any sort of constraint. I’m also still largely ignorant about keys and scales, but that doesn’t stop me from playing all the time. I can play along with pretty much anybody and anything, just by ear and a measure of bravado. This is rock music after all. As long as youstrike the right pose, who cares what key you’re in?

In the 1980s I had a band called A Nation In Exile that played in and around Manchester to no great acclaim. I briefly played guitar in a great indie group called the Chrysalids, before I left to go off to Swansea University.

While there, I performed as a solo artist—stage name Bibi—and then when I moved to Athens, Ohio I joined a wonderfully weird noise band called Kid Panda Hands.

Since moving to Wisconsin in 2007 I have continued to write, perform and record original music. I play open mics as a singer songwriter and sometimes with the legendary Dave Steffen Band. I like to jam with friends in various smokey ensembles—Hey Coat, Danky Kang—and most recently, I played in a three-piece band called the Shebeegeebees.

I started writing Mission to the Stars: A Space Rock Opera in 2006 when I lived and taught in Martin, TN for a year. The idea was not fully formed when the first song came along—"the Creation Song”—but then when I moved to Wisconsin in 2007, I came up with more songs, such as “the Chosen One” and “Lost in Space,” which gave me a theme, and gradually a narrative started to emerge. I worked with drummer Mike Berchem to develop the songs and the characters, and after a couple of years we were ready to go public. I wrote up a stage play that weaved the songs into a story about our heroes, Apollo Neumann and Walter Ego (Apollo’s inner voice), and their adventures in space. Then we recruited a band made up of local musicians, some singers to sing the songs, and a couple of local amateur actors/comedians to act as narrators. All fun. No money. Lots of cool artistic collaboration. No pressure.

The first full performance of the piece occurred in 2011 at EBCO, a small community theater in Sheboygan WI, and featured Drew Fredrickson (Jetty Boys) and Jared Beckman (Cedarwell) in the lead roles. In 2012, a new outdoor version of the show—Mission to the Stars: Blast Off—premiered on the Fountain Park stage, as part of Sheboygan’s annual Earthfest. The last of the early performances—Mission to the Stars: The Sputnik Saga—took to same stage in 2013, featured Ross Fale (Plutoniates) as Walter Ego, a new story and a bigger stage show. More than a decade elapsed before the next show. In 2023, Mission Haus to the Stars: A Space Rock Opera, was staged at Lakeland University, featuring a cast of Lakeland students and a band consisting of local musicians, including local rock god, Dave Steffen, on lead guitar, and Doc Mock on bass, Ross Fale on drums, and Michael Murphy on synthesizer.

The music to the first Mission to the Stars album was professionally recorded in 2021 with Marc Golde at Rock Garden Studios in Appleton, WI. It features Woodie Larsen on guitar, Sheboygan native Mike Underwood on drums, and Marc Golde on bass, lead guitar and keyboards. The music is varied—a little proggy and psychedelic, heavy at times, a bit rock-and-roll whimsical at others—and it is beautifully produced with soaring guitar solos, classic Mellotron and Hammond keyboard sounds, and spacey sound effects courtesy of NASA.

The songs are arranged to tell a story, but the lyrics are meaningful on their own, rooted, mostly, in an exploration of human nature and the human condition. If you like Pink Floyd, Peter Hammill, T Rex and David Bowie, you will like this album.

The sequel, Mission 2 the Stars: King of An Alien Nation, was released in June 2024. Produced, again, by Marc Golde at Rock Garden Studios, it features the same basic band with some additional musicians and instruments, such as a pedal steel guitar, a brass section on one of the tracks, and a French horn solo on the closing number. Two songs showcase local favorites: the Plutoniate’s Ross Fale on drums and Steve Bossler on bass. The music is even more varied than on the first album, mixing classic rock, punky rock ‘n’ roll, proggy moments, indie pop, and protest songs. This is another concept album, proudly in the tradition of Sgt. Peppers, Ziggy Stardust, and the Wall. The songs are arranged to tell a story about a rebellion on an alien planet, where an angry King tries to impose his will on his people, but they can also be read as a topical commentary on modern life.

Work on the final part of the trilogy—Mission to the Stars: The Plague—is already underway.

Most of my recent recordings are available for purchase at Music Boxx Records in Sheboygan, WI, or Rushmore Records in Milwaukee, WI, or by contacting me directly.

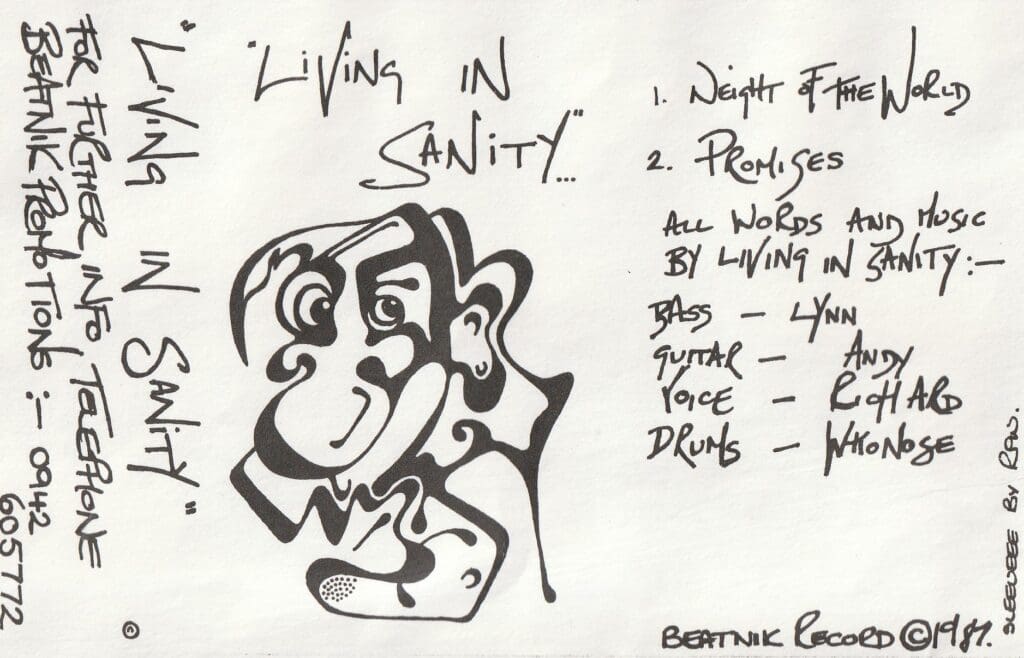

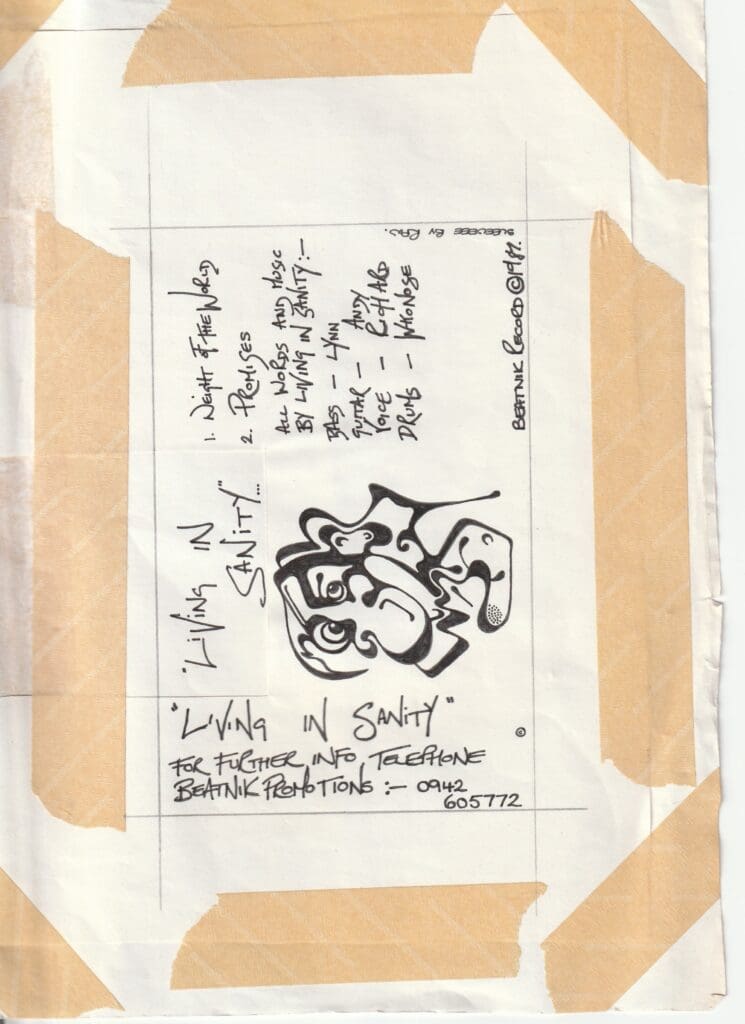

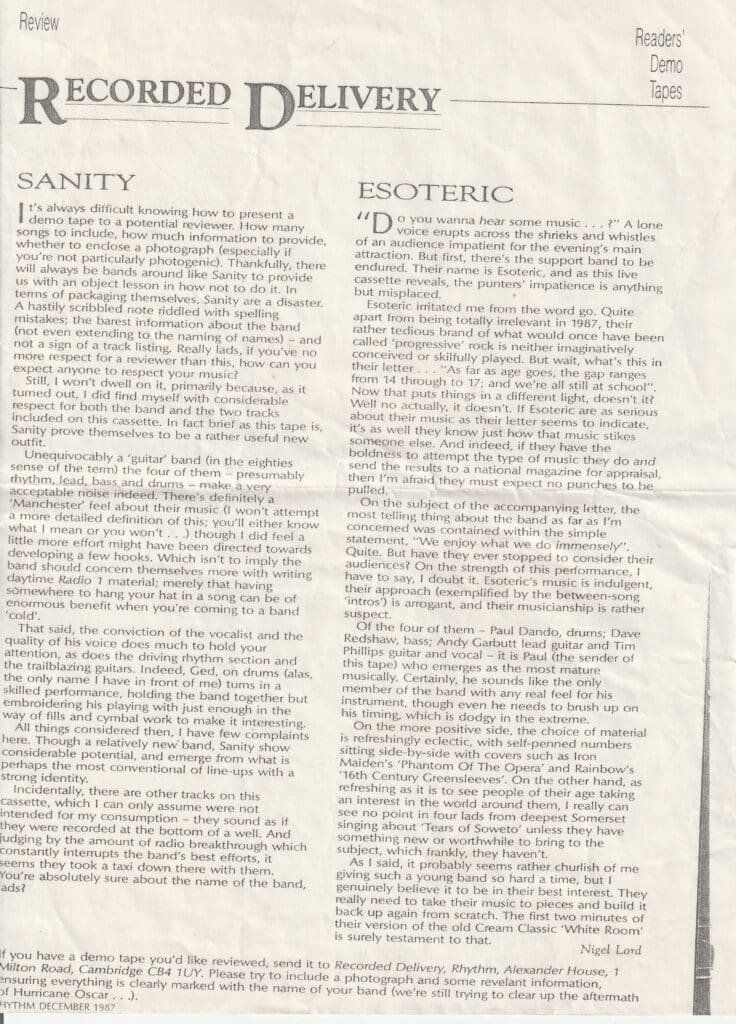

Living In Sanity

Living in Sanity was one of my earliest bands. As I remember it, this demo recording was made in The Kitchen, a recording studio located in Hulme, Manchester in the early 1980s. It was two flats knocked into one in the Hulme Crescent estate, an inner city housing experiment that was notorious for crime and nefarious behavior. At one point I looked out of the window to realize that my car had been moved. I pointed this out to the engineer and he nonchalantly said, "Yeah, looks like somebody borrowed it and brought it back."